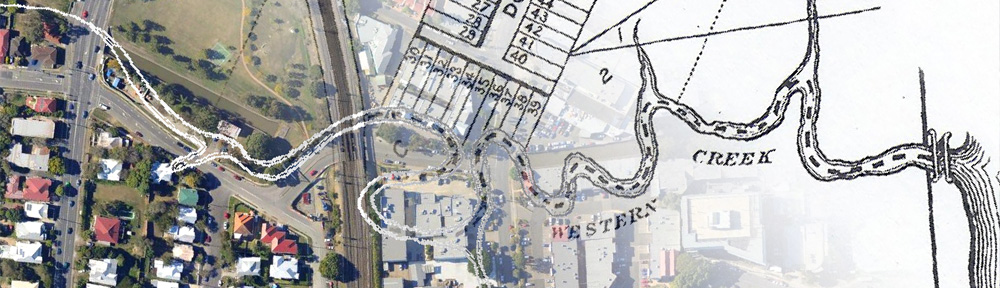

This is the fourth in a series of posts about Langsville Creek, which was Western Creek’s upstream neighbour on the Toowong/Milton Reach. Before reading this post, you may like to look at Part 1, Part 2 and Part 3 of the series.

Previously, on Uncovering Langsville Creek . . .

The first three episodes of this little mini-series have unfolded much like a daytime soap: the plot has thickened, but not much has happened. Well, without giving too much away, this is the episode where things happen. It is the murder-mystery end-of-season thriller. Characters will die, secrets will be revealed, and lost worlds discovered. But first, a brief recap.

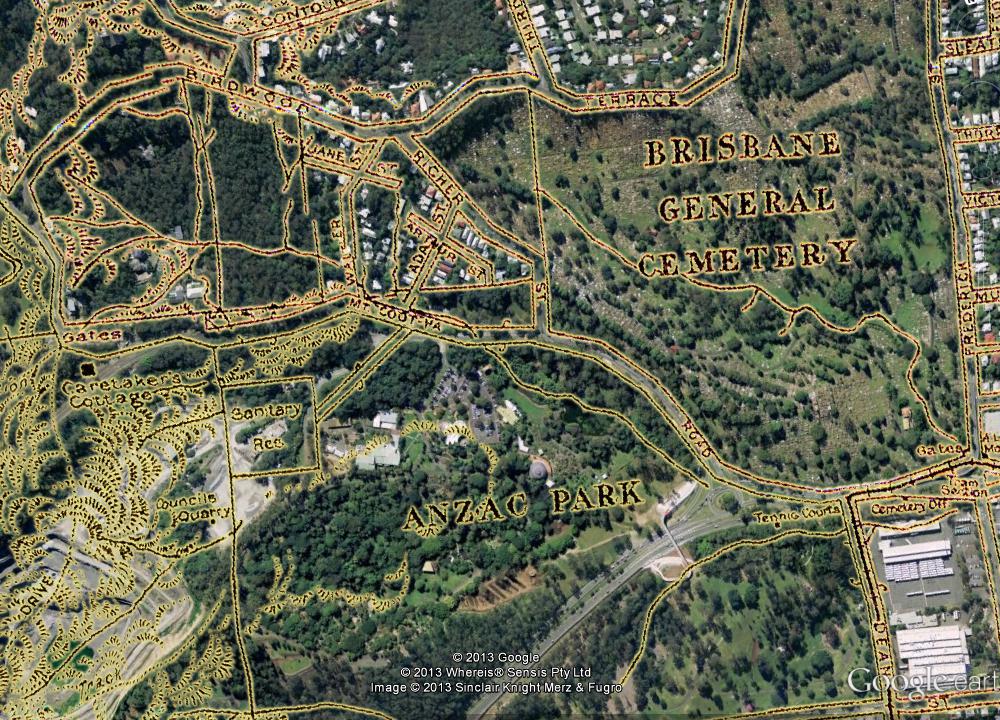

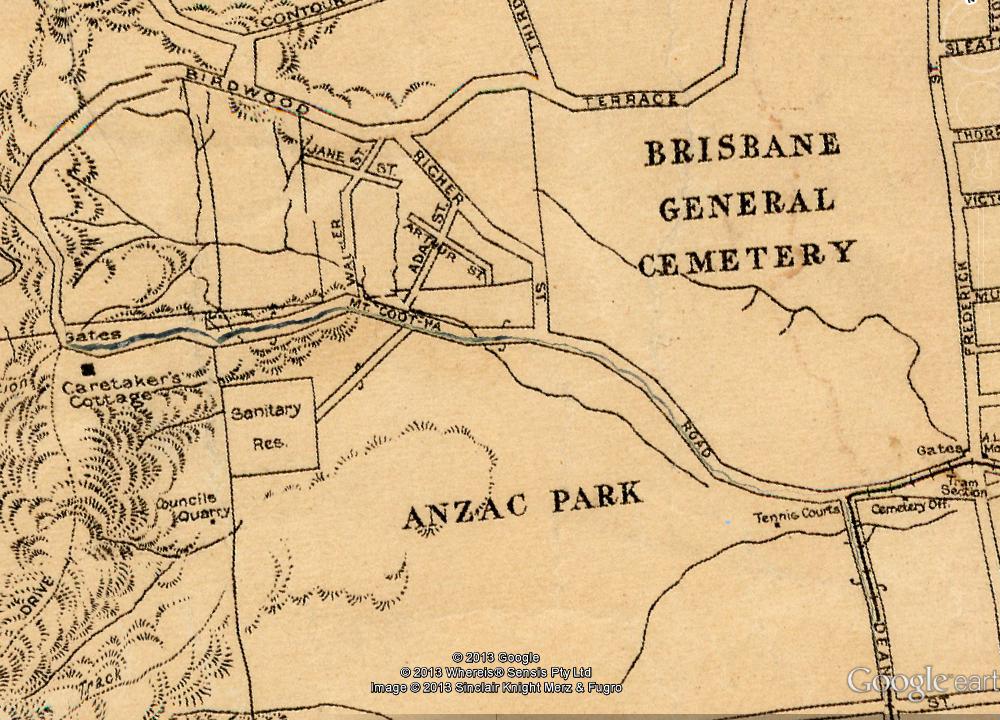

The previous episode introduced the map that you see below, which dates from 1929 and is the only one I have found that shows the upper reaches of Langsville Creek. We explored the stream that runs from the upper-left corner of the map into what is labelled as Anzac Park. Today, the area at the top-left is the Treetops on Birdwood estate, and the area labelled as Anzac Park is the Mount Coot-tha Botanic Gardens (hover your cursor over the image to see the modern landscape). In the slopes below Birdwood Terrace we found the headwaters of Langsville Creek more or less as they have always been — as gullies running through dry scrub. Immediately across the road, however, we found lush rainforest streams flowing into large lagoons, all part of the regulated water cycle of the botanic gardens.

Part of a map of Brisbane dating from 1929 (available online via Brisbane Images). The watercourses shown are the upper reaches of Langsville Creek. (Note that some distortions and artifacts emerged in preparing the map for Google Earth, most notably the giant crack running along Mount Coot-tha Road.)

At the end of the Western Freeway, where the entrance to the Legacy Way tunnel is still being built, the trail ran cold, and the Gardens stream came to an end. It is time, then, to move onto the other two streams — or one of them anyway, as I intend to drag this series out to a fifth installment (check back for it in six months or so). The stream we will look at today flows right through another of Toowong’s famous landmarks: the cemetery. Continue reading