From Red Jacket Swamp to Rosalie’s playground:

The story of Gregory Park

Page 1 – Page 2 – Page 3 – Page 4 – Page 5 – Contents

2. Best laid plans (1887 – 1903)

A tale of two shires (1887 – 1890)

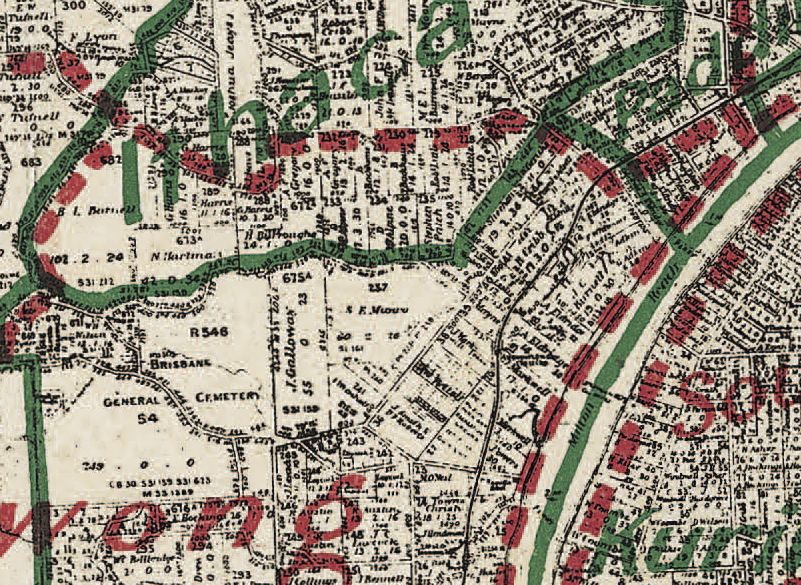

Until the formation of the Brisbane City Council in 1925, Western Creek flowed through two local government areas, these being the shires of Toowong and Ithaca.1 Toowong Shire fronted the river all the way along the Milton Reach, from Boundary Creek (where Hale Street is today) to Toowong Creek (near Gailey Road). The boundary between Toowong and Ithaca shires began where the railway line crossed Boundary Creek, and continued along the railway until it reached Baroona Road, then known as the Boundary-road because it divided the two shires all the way up to the top of what is still called Boundary Road today. (Back then, Baroona and Boundary roads were joined at the upper end of Norman Buchan Park.)

Ithaca Shire was to the north of Boundary Road, taking in much of present-day Bardon, Paddington, Red Hill and Kelvin Grove, while Toowong Shire extended south-west to the top of the Taylor Range on Mount Coot-tha and then east to the river. To the west lied the parishes of Enoggera and Moggil. The dotted red line on the map below shows the boundary of Ithaca and Toowong shires, beginning on the railway line at the top-right, and continuing along Baroona/Boundary road until it reaches Stuartholme Road at the top-left.

Part of a map showing old and new local government boundaries when the Brisbane City Council was established in 1925. The dotted red line is the original boundary dividing Ithaca and Toowong shires, beginning on the railway line at the top-right and continuing along Baroona and Boundary roads until it reaches Stuartholme Road at the top-left. (Brisbane City Council Archives)

The point of this local geography lesson is that Red Jacket Swamp, and the remainder of Western Creek to the river, was in the Shire of Toowong, but Western Creek immediately upstream of the swamp was in the Shire of Ithaca. So while the swamp itself was squarely within Toowong’s jurisdiction, the water (and everything else) flowing into it came courtesy of the Ithaca ratepayers in Rosalie. (Further upstream, the creek was again in Toowong Shire, but we needn’t worry about that now!)

Despite the obvious potential for fights about who was responsible for the state of the swamp, things began in a spirit of cooperation. In July 1887 the Toowong and Ithaca councils appointed committees to meet with each other and discuss the drainage of the swamp,2 and by 1889 they had reached agreement on the design of the drain under Baroona Road that would connect the future drainage schemes of the two shires.3 However, this promising start was to be only the first chapter of a protracted and painful saga that probably outlived many of the councillors themselves.

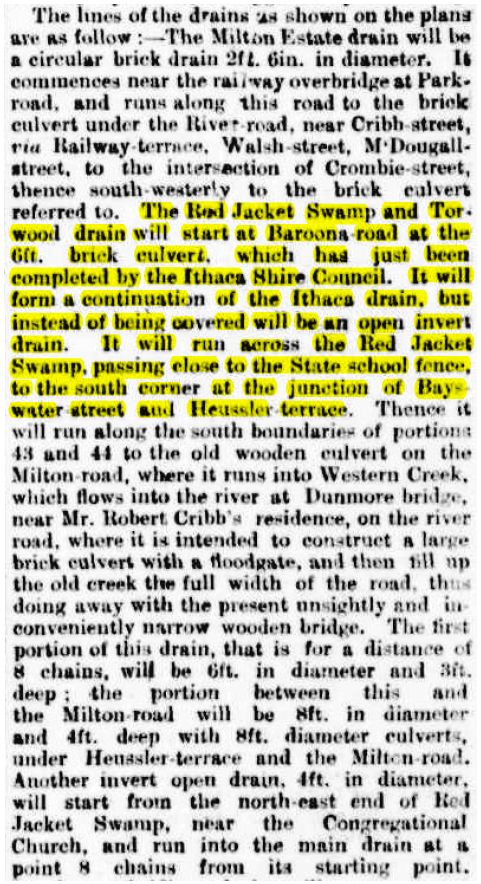

By October 1890, Ithaca Shire had developed a scheme for the drainage of Rosalie and had spent around £4,000 on works that included the drain under Baroona Road.4 The Toowoong Shire had also been busy developing plans for a whole-of-shire drainage scheme, which included main drains for the Milton Estate, Red Jacket Swamp, Torwood, Sylvan Road and Sherwood Road, as described in the following excerpt from the Brisbane Courier:

Clipping from The Brisbane Courier, 17 October 1890, describing the proposed Toowong Drainage Scheme. (Trove)

Toowong’s grand drainage scheme immediately hit two snags. The first was its price tag: an estimated £12,000, which was beyond the council’s means and would necessitate a government loan. More seriously though, much of the community strongly opposed the proposal for an uncovered drain across Red Jacket Swamp. The next few years saw a succession of petitions and public meetings in which ratepayers insisted on a covered drain and pleaded with the council to borrow the money needed to build it.5

A vexed matter (1892 – 1895)

While Toowong’s drainage plans had stalled, the sewage continued to flow from Rosalie with increased efficiency, only to accumulate in Red Jacket Swamp. The stench got worse, diphtheria cases became more frequent, and the ratepayers’ patience wore thinner. In May 1892, the Toowong North Ward Progress Association took up the case and convened a meeting “to discuss the vexed matter of the Red Jacket Swamp”.6 One speaker remarked that “There was no person coming into that neighbourhood and seeing the swamp but voted it a disgrace to the locality”. Another described the swamp as “a deathbed and a fathomless morass, instead of a recreation reserve, under which name it was held by the Toowong Shire Council.”

In August 1892 the Toowong Council minutes (which have survived only in the pages of The Brisbane Courier) record that a motion was moved by Sir Augustus Charles Gregory7 that “the improvement of the drainage of the Red Jacket Swamp as recommended by the shire engineer be carried into effect”. The motion was seconded and carried, but here the trail goes cold. For the remainder of 1892, and the whole of 1894 and 1895, neither the condition of the swamp, nor the matter of its drainage, is discussed in the council minutes or elsewhere in The Brisbane Courier.8

What might account for the sudden absence of discussion about the swamp? Explaining the matter to the Home Secretary in 1896, Councillor G. A. W. Kibble offered the following, somewhat cynical version of events:

. . . the Toowong Council had gone to the ratepayers on the subject of the continuation of the drain and had been defeated. The council wanted the drain to be an open one, but the ratepayers would not agree to this, and wanted a covered drain, and finally decided to have no drain at all.9

Perhaps the council and the ratepayers had indeed reached a stalemate. But other events may also have had a bearing. Firstly, the Australian banking crisis of 1893, which happened in parallel with financial crises in the United States and other parts of the world,10 would have dried up the funds available for major public works. Secondly, there was the Great Flood — or Floods — of 1893. Three major floods occurred in February of that year, including the second highest ever recorded (8.35m above low tide on the Port Office gauge, just under the event of 8.43m in 1841), followed by another in the unlikely month of June. Anyone who was around in January 2011 (or 1974 for that matter) will know that floodwaters are not pleasant, and the mud they leave behind is even worse. But the floodwaters and heavy rain in 1893 would have nonetheless helped to flush out the stagnating swamp. In addition, the cost of repairing damage caused by the floods would have further diverted funds away from projects such as the Red Jacket Swamp drain.

Whatever the case, the respite was not to last, as the wrath of the swamp, and of the ratepayers, would soon return with a vengeance.

Tides of discontent (1896)

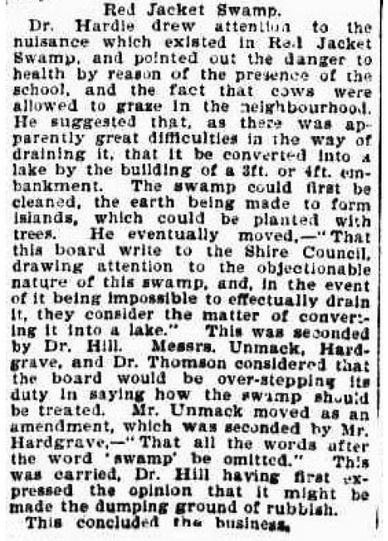

The issue of the swamp and its drainage came alive again, at least within the pages of The Brisbane Courier, in March 1896 when it was discussed at the fortnightly meeting of the Board of Health:

A clipping from The Brisbane Courier, 18 March 1896, reporting on a meeting of the Central Board of Health. (Trove)

This elicited a letter to the editor from Reverend John W. Roberts, whose sermons at the Milton Congregational Church (which was located at the corner of Haig and Baroona roads) were frequently graced by the noxious odours of the swamp:

It is high time something was done to improve this abominable spot. It is a disgrace to our city that within two miles of the General Post Office there should be in the populous suburb a pestilential swamp covering ten acres or more. The effluvium that rises from it, especially at night, is often positively sickening. The swamp is a great cesspit, in which the house drainage and the road washings from the surrounding hills collect. Here it stands, for weeks together slowly evaporating and depositing a filthy silt. Lately this has been more than usually bad. The channels have been choked with weeds and refuse for months past.11

The Reverend was sceptical, however, about Dr Hardie’s proposal to turn the swamp into a lake, drawing attention instead to the recreational and economic potential of the site:

I should prefer an open stone drain large enough to carry off flood-water, extended right down to the river, and locked. As the swamp is shallow, it might be filled gradually, not with rubbish, but with material obtained from cutting down some of the steep-grade roads near. If this were done, and a fence erected, it might be made a good sports ground or grazing paddock.12

In June 1896 the Toowong Shire Ratepayers Association appealed to the Central Board of Health, explaining that “So serious is the matter that when Mr Hodgkinson was Minister for Education he visited the place and seriously mooted the idea of having the state school, which overlooks the swamp, removed from its neighbourhood”.13 But the letter went on to explain that the council was too heavily in debt to finance a new drain. As before, the council would need to seek a loan from the government. For residents such as Reverend Roberts, this was no excuse for the council’s inaction:

In the opinion of old residents, the Red Jacket Swamp is in a filthier condition now than they have ever known it. . . . Nearly two months ago, in response to a mild epistle from the Board, the Toowong Shire Council said they would clean out the channels in the swamp, and thus allow the water which has been stagnating for the last six months to run off. What has been done? Absolutely nothing. The channels have never been touched, and are still choked with filth.14

Finally, in June 1896 a dialogue on the matter was established with H. Tozer, the Colonial Home Secretary, in the form of a deputation representing the Toowong Shire Council, the Ithaca Shire Council and local ratepayers.15 Toowong Councillor A.C. Gregory explained to Mr. Tozer the nature of the problem, and outlined two possible schemes to address it, one for a drain to Milton Road, and the other for a drain all the way to the river:

Regarding the drain to the river, he pointed out that at present the tidal waters came into the swamp, and the salt water killed the vegetation, and so caused it to fester and give off unhealthy odours. It would be necessary, if the drain was taken to the river, to put a lock on the end of it, to prevent the tidal water coming up.16

The meeting went well, although unsurprisingly the more modest of the two proposals appears to have been adopted, as the Toowong Shire Council quickly set about estimating the likely costs not only of an open drain 7ft wide and 2ft 6in deep from Baroona Road to Milton Road, but also of “filling up the swamp 18in” and constructing “bridges at Heussler terrace [Haig Road] and Milton-road, and a tide trap at the Milton-road”.17

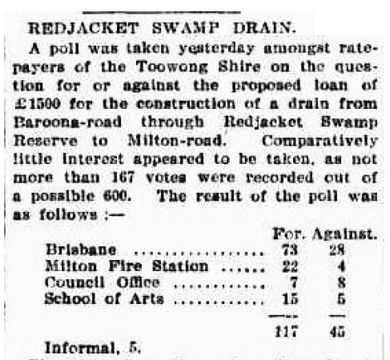

The predicted costs were £1458 to drain and fill the swamp to Heussler Terrace, and £789 to take the drain to Milton Road — a grand total of £2247. The Government agreed to contribute one third of the cost in cash and grant a loan, payable over 30 years, for the remainder.18 On 19 November 1896 a proposal to borrow £1500 was put to the ratepayers. The turnout for the vote was underwhelming, but the result was emphatic. Despite the drain on offer being an open one, the ratepayers voted decisively in favour of the loan. Perhaps the prospect of another few years with no drain at all was too much to bear.

Building the drain (1897 – 1901)

The council moved promptly to apply for the loan to build the drain, but it was not until October 1897 that a tender was accepted to commence work. Despite some interruptions due to flood in January 1898, the drain through Red Jacket Swamp and to Milton Road was completed in March 1898. Progress had also been made on filling up the swamp, using earth cut from Howard and Thomas Streets:

. . . by the beginning of April the filling in had been completed between Baroona-road, on the one side, and Bayswater-street, on the other, to a line from the north-east corner of the Milton State School reserve across to a point about six chains westerly from the Milton Fiveways. A portion of Bayswater-street, which was practically a piece of the swamp land, had to be filled. . .19

But costs had blown out, and in April 1898 the filling work ceased. Other work also remained to be done, such as the construction of a water-table (an open excavated channel) “from the Junction of the main drain near the State school reserve, and running parallel with Heussler terrace.” This work was expected to “have the effect of draining the whole of the remaining portion of the swamp”.20

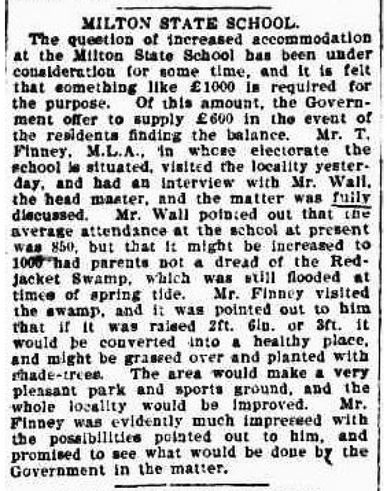

Rosalie now had a half-drained, half-filled-in swamp. Progress had been made, but the nuisance persisted, and there were continuing complaints about the condition of the swamp and its impacts on health, particularly that of the school students. At the same time though, the recreational potential of the site was increasingly being emphasised:

The need to secure such recreational spaces was also being recognised in the context of the rapid expansion of the city:

Brisbane is fast taking its place as a great centre of population, and unless the keenest vigilance is exercised the metropolis will grow, with but little provision for breathing spaces. . . . The Western suburbs have a distinct grievance in that the young folk cannot play football or cricket without trespassing on private property, so scanty are public places dedicated to the public; but Rosalie and Milton especially are in trouble because an evil swamp lies in the way of both health and exercise.21

As always, one other thing also stood in the way: money, or rather the lack of it. Needing another loan to complete the filling in of the swamp, the Toowong Shire Council in 1901 led a second deputation to the Home Secretary, Hon J. F. G. Foxton. This time, however, they also had in mind another source of funds. The Toowong councillors contended that the Ithaca Shire Council should pay for some of the work, given that “Drainage into the swamp came from about a hundred houses in the Ithaca Shire”.22 Furthermore, as A. C. Gregory quipped to the Home Secretary, not only was the swamp a nuisance to Ithaca, but “Ithaca [was] a nuisance to the swamp”.23

Unsurprisingly, the Ithaca Shire Council would have nothing of it,24 no doubt believing that the £4,000 or more that they had spent on the Baroona Road drain ten years previously (an amount which the Toowoong council had still not matched) was an ample contribution to the local drainage scheme.

Gregory’s Mud Hole (1901 – 1903)

What happened in the few years following 1901 is not very clear, at least not from the council records printed in The Brisbane Courier. It appears that little more in the way of filling in had been done by January 1902, as at this time the idea of creating a lake was again mooted by the Board of Health.25 In May 1902 Alderman John MacDonnell brought forward a motion to borrow £1000 to fill in the swamp — a motion that appears to have been rejected.26 In terms of drainage works, there was a motion put forward in September 1903 “to procure an estimate of the price of a flood-gate at the entrance to the Red Jacket Swamp sewer, capable of keeping out the salt water”,27 and in July 1904 there was a motion to create a concrete invert drain from the fiveways to the main drain in the swamp.28 I have not yet found the outcome of either of these motions.

Progress on draining and filling the swamp might have slowed, but an administrative milestone was reached in July 1903, when the ‘Red Jacket Reserve’, as it was increasingly being called, was declared a recreation reserve and given to the control of the Toowong Shire Council.29 In July 1905, the council moved to rename the reserve in honour of one of their most distinguished and longest-serving members. At the Council meeting of Tuesday 13 June, Alderman J. F. Bergin gave notice of a motion “That in future all moneys spent on the Red Jacket Reserve be declared a charge upon the general revenue of the town, and that the name of the reserve be altered from Red Jacket Swamp to Gregory Park”. Alderman A. C. Gregory’s response at the meeting suggests that the new title might have been somewhat premature: “I don’t want to father that place”, he said. “Better modify it to ‘Gregory’s Mud Hole’”.30

About two weeks later, Sir Augustus Charles Gregory died in his Rainworth home, aged 86. Despite his reservations, which he had probably expressed only partly in jest, his name would indeed become synonymous with the mud hole that for half a century had been known as Red Jacket Swamp. At the next council meeting on Tuesday 11 July, Alderman Bergin’s motion was carried, and “the name of the Red Jacket Reserve was changed to Gregory Reserve”.31

Next page

Page 1 – Page 2 – Page 3 – Page 4 – Page 5

Contents

Notes:

- Ithaca was actually a larger ‘division’ until it was split in 1887 into the Shire of Windsor, the Division of Enoggera, and the Shire of Ithaca. ↩

- The Brisbane Courier, 8 July 1887, p6. ↩

- The Brisbane Courier, 22 November 1889, p6. ↩

- The Brisbane Courier, 10 December, p5; also see 7 July 1896, p4. ↩

- The Brisbane Courier, 3 November 1890, p4; 28 January 1891, p3; 18 September 1891, p6; 15 August 1892, p3. ↩

- The Brisbane Courier, 12 May 1892, p6. ↩

- Sir Augustus Charles Gregory (1819–1905) had a distinguished career as an explorer and later as the Surveyor General of Queensland. He built the residence ‘Rainworth’ (still standing today on Barton Street) in 1862 and lived there until his death in 1905. ↩

- Unfortunately, according to the Brisbane Archives, no other record of the Toowong Shire Council meetings has survived except for the reports in The Brisbane Courier. ↩

- The Brisbane Courier, 24 July 1896, p7. ↩

- Wikipedia, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Australian_banking_crisis_of_1893. Accessed 26 February 2012. ↩

- The Brisbane Courier, 20 March 1896, p2. ↩

- The Brisbane Courier, 20 March 1896, p2. ↩

- The Brisbane Courier, 8 June 1896, p6. ↩

- The Brisbane Courier, 10 June 1896, p7. ↩

- The Brisbane Courier, 24 July 1896, p7. ↩

- The Brisbane Courier, 24 July 1896, p7. ↩

- The Brisbane Courier, 1 August 1896, p4. ↩

- The Brisbane Courier, 4 September 1896, p4. ↩

- The Brisbane Courier, 23 May 1898, p7. ↩

- The Brisbane Courier, 23 May 1898, p7. ↩

- The Brisbane Courier, 20 July 1901, p4. ↩

- The Brisbane Courier, 1 August 1901, p7. ↩

- The Brisbane Courier, 1 August 1901, p7. ↩

- The Brisbane Courier, 22 November 1901, p6. ↩

- The Brisbane Courier, 23 January 1902, p4. ↩

- The Brisbane Courier, 23 May 1902, p4. ↩

- The Brisbane Courier, 11 September 1903, p7. ↩

- The Brisbane Courier, 13 July 1904, p6. ↩

- The Brisbane Courier, 2 July 1903, p4. The proclamation of a recreation reserve at Red Jacket Swamp was also reported in The Brisbane Courier on 5 August 1887 (p7). I don’t know if this was for a different portion of land to that proclaimed in 1903, or if there difference is merely that in 1903 control of the land was handed from the Commonwealth over to Toowong Shire Council. ↩

- The Brisbane Courier, 14 June 1905, p6. ↩

- The Brisbane Courier, 12 July 1905, p6. ↩

Last modified: August 26, 2023