John Oxley and the chain of ponds

Where do we begin? A tale of two city monuments

The monument at North Quay commemorating Oxley’s landing. The text reads: Here John Oxley landing to look for water discovered the site of this city. 28th September 1824.

The monument at Milton commemorating John Oxley’s landing. The text reads: On 28 September 1824, Lieutenant John Oxley, Surveyor-General of New South Wales, landed hereabouts to obtain fresh water from a nearby stream declaring it to be “by no means an ineligible station for a first settlement up the river”.

History is nearly always subject to some level of interpretation. But can there be many cities in the world where you can find not one but two monuments, in quite separate locations, marking the spot where it all began? In Brisbane you can find just this — one in North Quay near Makerston Street, erected in 1928,1 and another erected sixty years later and one mile upstream where Coronation Drive overlooks the mouth of Western Creek (known today as Milton Drain).

Until very recently I didn’t know that either of these monuments existed, despite having travelled past them countless times. I came across the boulder at Milton not long after I started exploring and learning about Western Creek. But if not for the instructions provided in Matthew Condon’s book Brisbane,2 I doubt I ever would have found the obelisk at North Quay. Once you know where to look, you can’t miss it; but in all likelihood you have never had cause to walk past it. And despite its imposing size and grand setting, it has been all but swallowed up by the surrounding vegetation, roads and guardrails. Its big, bold capital letters shout “Hey, look at me, I’m important!”, but everything else suggests that it has been neglected and forgotten, as if the world around it has somehow moved on.

The John Oxley memorial at North Quay, seen from the path behind it leading to the riveside bikepath.

So what happened? Is this any way for a city to treat its history? For the full story behind this monument — or about as much of the full story as could be told so long after the fact — I can only recommend reading Matthew Condon’s Brisbane3 (or at least flicking through to the history bits like I did!). To put it briefly though, the North Quay obelisk was the brainchild and pet project of Dr Francis William Sutton Cumbrae-Stewart, who was a lawyer, lecturer, university administrator and founding president of the Queensland Royal Historical Society. After looking at John Oxley’s field book, Cumbrae-Stewart convinced himself — and apparently others — that Oxley ‘discovered’ the future site of the city upon landing and finding water at North Quay on 28 September 1824. Cumbrae-Stewart proposed a memorial to mark the centenary of this historic event, and through his persistence, along with a few connections in high places, he eventually saw his vision realised. The obelisk was unveiled sometime in 1928, though exactly when, and by whom, nobody seems to know.

And so the obelisk stood, apparently unchallenged, until in 1950 a historian by the name of T.C. Truman published a series of four feature articles in The Courier Mail under the title “Rewriting the history of the birth of Brisbane”. In the third article,4 through a careful analysis of Oxley’s field book, Truman more or less demolished Cumbrae-Stewart’s theory about the landing at North Quay. He showed instead that Oxley’s landing and his discovery of fresh water most likely happened somewhere in the vicinity of Western Creek. But strangely enough, it seems that no-one had the heart to remove or rebadge the memorial at North Quay. Perhaps even back then not enough people knew or cared about the memorial for its inaccuracy to matter.

Finally in 1988, amidst Australia’s Bicentenary celebrations, a new monument commemorating Oxley’s landing was established along Coronation Drive, this time carrying the authoritative blessing of the Australian Institution of Surveyors. This stone is even bigger than the one at North Quay. Below it are the remains of a restaurant that used to be called ‘Oxley’s on the River’. And across the road there is a whole office block named the John Oxley Centre, where at entrance you can see a strange flag-like installation embossed with snippets from Oxley’s diary.5 Resistance is futile: THIS is where Oxley really landed. Don’t listen to the obelisk down the road: it doesn’t know where it’s at. It doesn’t even know about commas!

What are we to make of the misplaced monument that time and punctuation forgot? Why did it stand uncorrected for so long, and why is it still there today, now that a new memorial has been established? I will leave these questions for the reader to ponder, for answering them is not the purpose of this essay. Instead, I want to go back to September 1824 and examine the events in Oxley’s diary in light of all that we know about Western Creek. Whether or not we take Oxley’s landing on 28 September 1824 to be the ‘discovery’ of Brisbane, I find it quite thrilling to imagine John Oxley (along with Allan Cunningham) roaming around what would one day become Milton and Rosalie, surveying the landscape in search of fresh water. Our own exploration of Western Creek would be incomplete without us doing all we can to retrace his steps and imagine what he might have seen.

The creeks of the Crescent Reach

In September 1824, John Oxley, then the surveyor-general of New South Wales, embarked on his second expedition up the Brisbane river, having first explored it in December 1823.6 He had returned to Moreton Bay to assist Lieutenant Henry Miller in establishing a new convict settlement, and to further explore the river in the company of the Colonial botanist Allan Cunningham and Lieutenant Butler of the 40th Regiment.

At Oxley’s recommendation, a site at Redcliffe Point was chosen for a first settlement. But there was also interest in establishing a settlement along the river, and one of the goals of Oxley’s expedition was to scope out a suitable site. Oxley set off on Thursday, September 16th and by Tuesday the 21st had taken the boats as far upstream as the Mount Crosby area, at which point the boats could go no further due to the “very low and depressed state of the stream” (this and other comments in Oxley’s diary indicate that the area was in the grip of drought). He and Cunningham continued on foot up Mount Crosby and Pine Mountain to see the view to the west, before commencing the return journey back down the river on Saturday the 25th.

On the evening of Monday the 27th, Oxley’s party came to what he described as the ‘Crescent Reach’. This is what we would today call the Milton reach, beginning where Toowong Creek meets the river and continuing all the way to North Quay. Here Oxley expected to find fresh water, and so intended to camp for the night. In choosing a campsite, he was careful to keep some distance between his party and the local Turrbal people, having already encountered trouble with them earlier in his journey:

We saw at the commencement of the reach on the left bank a very large assemblage of natives in the same spot as we saw them last year. We landed about half-mile below this encampment on the same side of the river, there being a small creek between us, which I hoped would prevent them visiting us.7

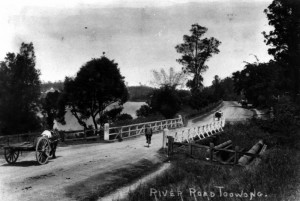

The bridge over Langsville Creek, Auchenflower, ca. 1914. John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland, Neg: 10579.

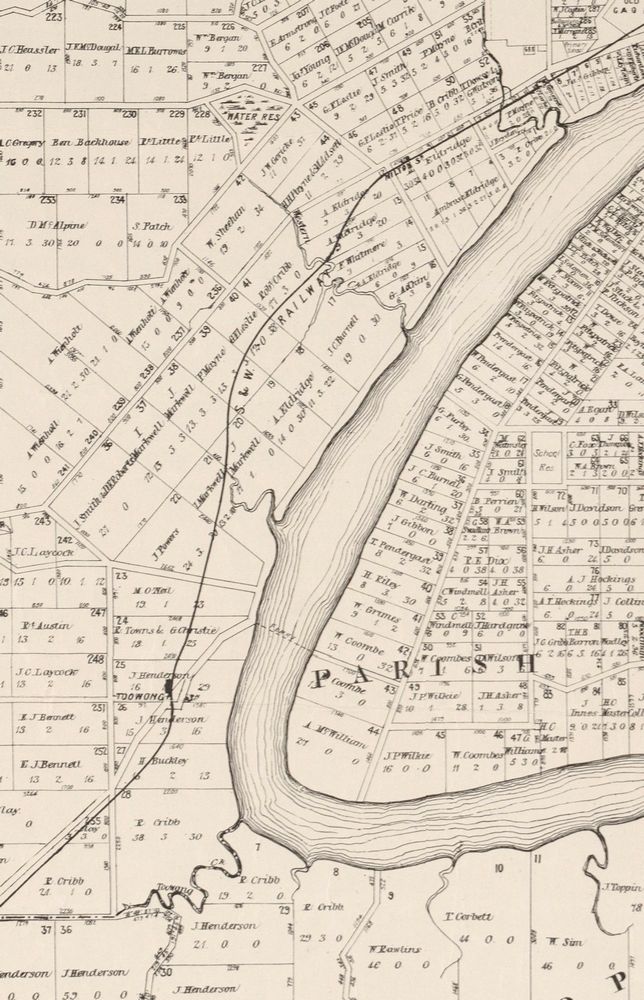

The small creek by which they camped was the inlet that later became known as Langsville Creek or Patrick’s Creek. This watercourse flowed through what is now Moorlands Park and under the ironically named Land Street, and met the river near where Patrick Lane meets Coronation Drive. Its meandering branches are depicted clearly on McKellar’s 1895 map of Brisbane, as shown below. The second map below dates from 1884 and shows the entire Crescent Reach and its four creeks, starting with Toowong Creek at the bottom, followed by Langsville Creek, Western Creek, and finally Boundary Creek, which for a time marked the western limit of Brisbane Town.

Langsville Creek, Auchenflower, depicted on McKellar’s 1895 map of Brisbane (sourced from the Queensland Historical Atlas)

The Milton Reach of the Bisbane River, depicted on a map produced by the Queensland Surveyor General’s Office in 1884 (‘Moreton 20 chains to an inch. Sheet 1B’. National Library of Australia: http://trove.nla.gov.au/work/11526397)

Camping on the far side of Langsville Creek did little to keep the natives at bay. While Oxley and Lieutenant Butler went in search of fresh water (which they failed to find), leaving Cunningham to set up the campsite, a large contingent of the locals descended upon the camp. Among them was one whom Oxley recognised for stealing his hat at Breakfast Creek ten days earlier. “He was a fine, athletic man”, Oxley noted, “as indeed they all were”. After hurling a piece of wood at Oxley (and missing), the man prepared to throw a stone at Lieutenant Butler, who fired his gun and struck the man on his left arm and side. This put an immediate end to the altercation, but howls from the camp upstream were heard through much of the night. The following morning, Oxley’s men decided that the a quiet exit would be the best course of action:

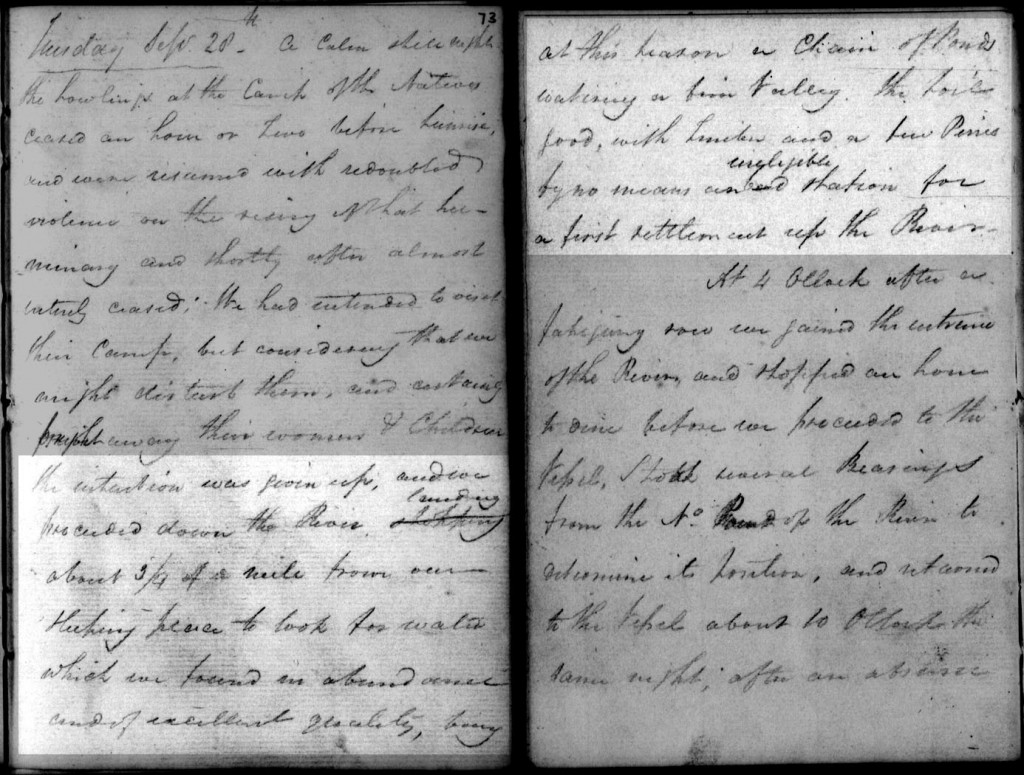

We had intended to visit their camp, but considering that we might disturb them, and certainly fright away their women and children, the intention was given up, and we proceeded down the river, landing about three quarters of a mile from our sleeping place to look for water which we found in abundance and of excellent quality, being at this season a chain of ponds watering a fine valley. The soil good, with timber and a few pines, by no means an ineligible station for a first settlement up the river.

The pages containing this passage in Oxley’s field book (which is held today in the State Library of New South Wales and can be viewed online), are shown below.

Pages from John Oxley’s diary of his expedition up the Brisbane River in September 1824 (Mitchell Library, State Library of NSW: ML C246)

By four o’clock the same afternoon, following a long row against the tide, Oxley’s party had reached the bay, and at around 10 o’clock that night they arrived at Redcliffe, where Oxley’s boat was moored. Oxley said nothing more in his diary about the fine valley or the chain of ponds that he saw as worthy of supporting a new settlement. These few lines form the entire basis for both of Brisbane’s foundation stones. Given how few details there are to work with, we should hardly be surprised that people have reached different conclusions about where Oxley landed and found water on 28 September 1824. But while can never be absolutely sure about where he landed, we do have enough clues to make a solid educated guess.

Joining the dots

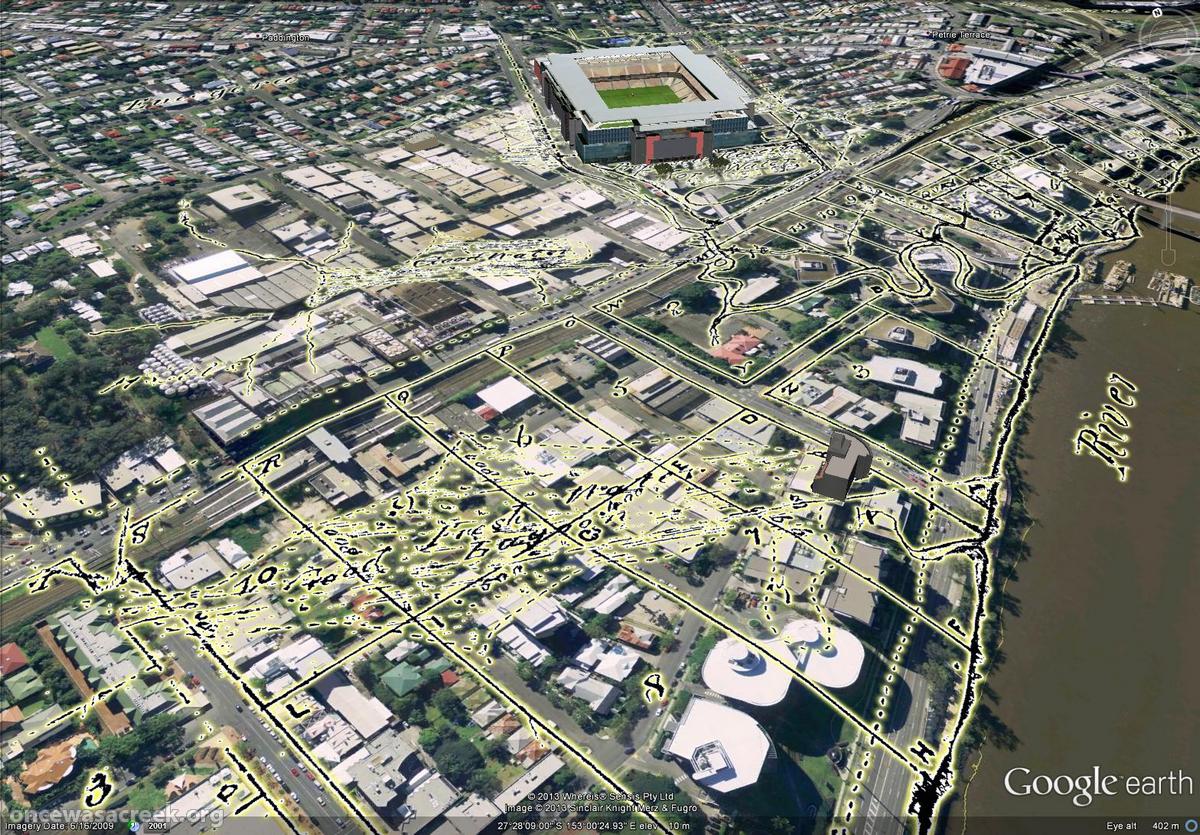

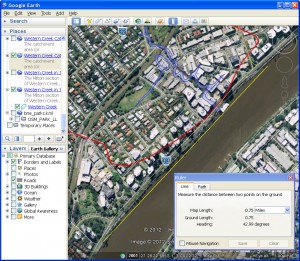

Assuming that Oxley’s judgements of distance were accurate (and they should have been, given his experience as a seaman and surveyor), we need nothing more than a map and a ruler — or better still, Google Earth — to figure out where he landed. Using the ruler tool in Google Earth, you can check for yourself that the distance between the start of the Toowong reach and Patrick Lane, where Oxley camped, is indeed about half a mile (~800 metres). Following the river for another three quarters of a mile puts Oxley’s landing place somewhere in the vicinity of Park Road.

Park Road?! But neither of the two monuments is there! This is true, but the one at Milton is not far away (about 300 metres upstream), and its inscription permits some wiggle room thanks to the word ‘hereabouts’. I think the simplest supposition we can make is that Oxley saw Western Creek, and with the tide low,8 looked for the nearest convenient place to come ashore.

From here there are not many dots to join before concluding that the chain of ponds Oxley found was probably somewhere along Western Creek. We’ll join those dots in a minute, but first it’s worth exploring some other possibilities, if only to see if we can discount them.

If Oxley had walked down the river instead of heading back upstream to Western Creek, he would have first passed through what is now the Kings Row Office Park, which is bounded by Coronation Drive, McDougall Street and Cribb Street. There was once a lagoon that joined the river here and stretched all the way to the corner of Park Road and Milton Road. This lagoon is shown on James Warner’s map from 1850, annotated as “Good Fresh Water Lagoon”. However, this lagoon was probably dry when Oxley visited, or at best it would have contained the same water as that in the river, which evidently did not meet Oxley’s standards. During the summer of 1886, this lagoon dried up to such an extent that the land was subdivided, sold and built on without anyone apparently realising that it was ordinarily a water body.9 The drought that prevailed during Olxey’s 1824 visit had probably left the lagoon in a similar condition. And besides, a lagoon situated amidst such flat terrain could hardly match Oxley’s description of the ponds “watering a fine valley”.

The lagoon that once stretched between Cribb Street and Park road (foreground), and Boundary Creek, as depicted on a map from 1850.

A little further downstream was Boundary Creek, which meandered through the Coronation Drive Office Park and opened into a swamp where Suncorp Stadium is today. This is where Brisbane’s second cemetery was established. James Warner’s map from 1850 shows the swamp clearly, and also indicates an area near Officeworks as a source of “Good Water”. Near the stadium a small dam had also been built along a tributary of Boundary Creek: this was known as the Milton Water Reserve.

The swampy area of Boundary Creek, Milton, as depicted in 1850. The area was first used as a cemetery, and is now Suncorp Stadium.

Despite Boundary Creek having a relatively small catchment (the boundary of which can be defined approximately by Petrie Terrace, Musgrave Road, Enoggera Terrace, Latrobe Terrace and Given Terrace), there was evidently a good amount of fresh water in this area, at least when James Warner did his survey. Could there have been a chain of ponds here during the drought when Oxley visited? Maybe — but only if the ponds were springs fed by the underground water table, or if there was a spring somewhere upstream. Without an underground water source, the streams and ponds in such a small catchment would have dried up quickly without good rainfall. But then again, the same could be said of Western Creek, the catchment of which is only two or three times bigger. So perhaps there might have been a chain of ponds along Boundary Creek in 1824, nestled within the surrounding hills. I admit that I don’t have a strong argument to rule this out as the location of Oxley’s ponds, except to note that it is further than Western Creek from where Oxley apparently came ashore.

Brisbane’s first water supply: the Roma Street Reservoir, ca. 1862 (John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland, Neg: 147714)

Stretching Oxley’s legs (as well as our credulity) a little further, we could suppose that Oxley walked all the way to Roma Street, where he would have found a creek10 that was fed by a spring (the namesake of Spring Hill), and which ultimately became Brisbane’s first water supply. Fresh water in abundance, and in the very place where the town was ultimately established — these pieces of the puzzle fit. But from here it is nearly a whole mile back to Park Road where Oxley apparently landed. Surely a walk this far downstream, especially one that included a creek crossing, would have rated a mention when Oxley recorded the location of fresh water. Yet in his diary there is not even so much as a comma separating the landing and his discovery of the chain of ponds.

A monumental stuff-up

Of course, this problem of distance goes away if we suppose that Oxley actually landed further downstream. This is exactly what F.W.S. Cumbrae-Stewart did in order to support his assumption (and that’s all it appears to have been) that the site Oxley discovered was near North Quay. Though the obelisk ultimately ended up near Makerston Street, Cumbrae-Stewart’s original hypothesis, which he presented at a gathering of the Brisbane Women’s Club on 27 September 1924 to mark the centenary of Oxley’s discovery, was that the landing place was about a third of a mile (or half a kilometre) further upstream:

I hazard the guess … that Oxley landed at what is now known as Boundary Creek, and walked to a spot near Makerston Street. From the top of the bank water was seen in abundance in a chain of ponds watering a fine valley. That fine valley now runs through the heart of the city, and the chain of ponds which once extended from Roma-Street to Creek-Street are now filled in and covered with massive buildings.11

Recall that Oxley described his landing place as being about three quarters of a mile from his sleeping place at Langsville Creek. The distance from his sleeping place to Boundary Creek is more than a mile. For this to be his landing place, he would have had to misjudge the distance by about 0.4 miles, or around 650 metres. Put another way, this equates to about a 50% error on his estimated distance. It’s hard to believe that someone as experienced as Oxley could have got it this wrong. The monument at North Quay is further away still, and as Matthew Condon notes, it stands at the top of a steep and rocky cliff — one of the highest points along that part of the river bank, and surely one of the last places where someone in a rowboat would choose to scramble ashore. Then again, perhaps Cumbrae-Stewart didn’t really believe that Oxley landed here. Perhaps, as the quote above suggests, he believed this to be the vantage point from which Oxley saw the chain of ponds and the site of the city, having landed at some other place close by. In fact, the strange unpunctuated sentence on the obelisk could be read to mean just this. Maybe it was meant to be ambiguous all along to cover for Cumbrae-Stewart’s own uncertainty about where the obelisk should go.

Either way, the obelisk is in the wrong place. And yet there it stands, without so much as a supplementary footnote advising the unsuspecting reader that the correct site is a mile further up the river.

The chain of parks

Let’s return to the simplest interpretation of the events recorded in Oxley’s diary for the morning of 28 September 1824. Convinced that there must be fresh water somewhere along the Crescent Reach, Oxley landed just downstream of Western Creek, which he then followed inland to find the chain of ponds watering a fine valley. The question that follows is where were the ponds?

John Pearn, in his book Auchenflower – the suburb and the name, says of the ponds and the valley:

This reference is almost certainly that of the drainage area of Western Creek, now in the vicinity of Frew Park, the Milton Tennis Courts, Gregory Park and the grounds surrounding Milton State School.12

In another passage, Pearn also includes Milton Park in this drainage area.13 T.C. Truman, in his Courier Mail article in 1950, also highlights this area as a likely location of the ponds:

I am told by old residents that there were chains of waterholes connected by the Western Creek which had its rise in a swamp with the picturesque name of Red Jacket Swamp which has since become Gregory Park, next to the Milton State School. This creek used to flow through the areas now called Frew Park and Milton Park and came out at Dunmore Bridge, on Coronation Drive. The last part of it has been converted into a drain.14

We might call this the ‘chain of parks’ theory, and it has obvious appeal. It is easy to imagine a chain of waterholes extending from Gregory Park (which we know was once Red Jacket Swamp) through Frew Park, Milton Park, and even Dunmore Park (which also was once a swamp). If you were here during the floods of 1974, 2011 or even 2013, you might not need to imagine it at all. As for the ‘fine valley’, if we’re honest we have to acknowledge that the land is pretty flat in all directions until you come as far upstream as Frew Park, and it doesn’t really became ‘valley-like’ until you reach Gregory Park, where you can see the slopes of Heussler Terrace in one direction and Howard and Thomas Streets in the other. Still, there is enough overlap here with the chain of parks to keep this theory alive. But before we leap to conclusions, there are other things we need to consider.

The tidal reach

Remember that Olxey was not interested in just any old water: he was after fresh water, which he apparently found “in abundance and of excellent quality”. In trying to identify the location of the chain of ponds, we need to think about what sort of water might have been present in different parts of the landscape, and where it might have come from.

One source of the water in Western Creek is the river. The rise and fall of the river’s tides can be seen readily in Milton Drain, which over the course of a day can drop from being nearly full to all but empty. Even in Frew Park, if you peek through the drain covers you can see (or hear) the water at high tide coming up to within a couple of feet from the ground. The reach of the tidal waters must extend some distance into Gregory Park as well. In the late 19th century the tidal waters were entering Red Jacket Swamp and contributing to the stagnating soup of rubbish and organic matter. The Toowong Councillor A.C. Gregory (after whom Gregory Park was named) led a deputation to the Colonial Secretary in 1896 to request Government assistance in addressing the nuisance at Red Jacket Swamp. In outlining a proposed drain between the swamp and the river, Gregory explained,

. . . at present the tidal waters came into the swamp, and the salt water killed the vegetation, and so caused it to fester and give off unhealthy odours. It would be necessary, if the drain was taken to the river, to put a lock on the end of it, to prevent the tidal water coming up.15

Correspondence between Council engineers in the 1930s suggests that the tides even reach under Baroona Road.16 Under this tidal regime, there could not have been ponds full of pure, fresh water anywhere between the river and Gregory Park, because they would been inundated daily with brackish water from the river.

But this tidal regime would not have applied in 1824. In the 1860s, dredging works commenced in order to make the lower reaches of the river more navigable. The bar near the river mouth was removed, the flats near Eagle Farm and Pinkenba were deepened, and similar changes were made elsewhere.17 These changes would have facilitated the flow of water in both directions and significantly changed the tidal dynamics, causing the tidal reach to creep further and further upstream.18

So there is a good chance that Gregory Park and Frew Park would have been clear of the river’s influence back in 1824, allowing for freshwater ponds in this part of the creek. Otherwise, why would Red Jacket Swamp have been ‘reserved for water’, as it says on the very early maps?19

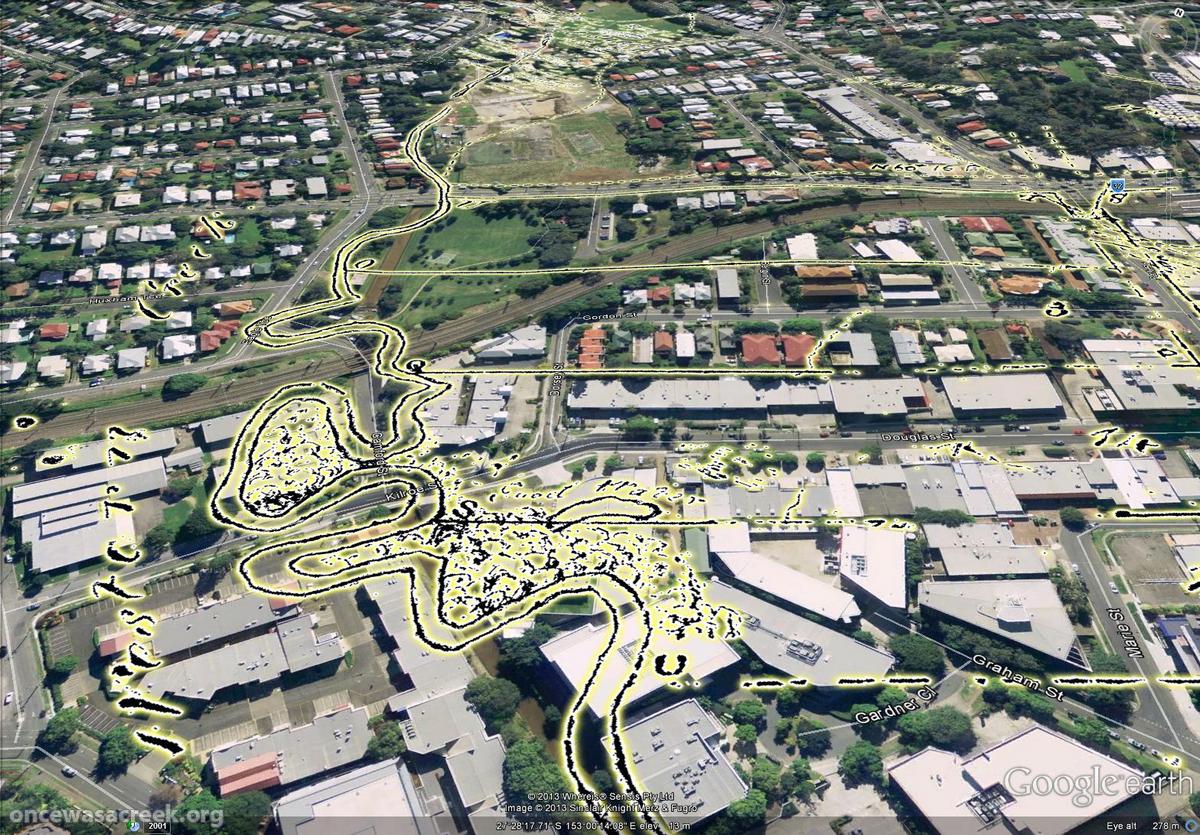

in fact, something on James Warner’s map from 1850 suggests that the creek was fresh even further downstream. At a swampy region just near where Kilroe Street is today, there is a small pond marked “Good Water”. Perhaps during wet periods the river itself was fresh here too, whereas during drought the tides would reach further, bringing salty water with them.

Western Creek as depicted on a map from 1850. In the foreground is a pond marked ‘good water’, and in the distance is Red Jacket Swamp. The rest of the map is discussed on this page.

The bottom line is, I don’t know whether the chain of ponds could have been as close to the river as the chain of parks is today. It seems plausible, but someone who knows more about the river’s history than me will have to chip in if we are to have a definitive answer. In the meantime though, we would do well to consider other possibilities.

A finer valley

Let’s suppose that the chain of ponds was a little further upstream. Following the course of the creek from Gregory Park through the Rosalie Swamp,20 we might imagine a series of ponds in the low-lying backyards along Elizabeth and Beck streets, continuing to the bottom of the Government House grounds and Norman Buchan Park, where, lo and behold, there is a pond even today. What’s more, the surrounding hills here are higher and steeper than those around Frew Park and Gregory Park, and they can be seen extending all the way up into Rainworth and Bardon — a fine valley indeed!

At this point, it would be remiss of me not to mention the final twist in Matthew Condon’s investigation into John Oxley’s landing, described in his book Brisbane. A year after beginning his investigation, Condon was contacted by David Barr, a Brisbane truck driver with an interest in finding the true locations of Oxley’s landing and the chain of ponds:

David’s theory is that the ‘beck’ or stream and sequence of ponds, like lovely baubles on a string, that lured Oxley deeper into the fine valley, ran from present-day Gregory Park (Red Jacket Swamp) then between Beck and Elizabeth streets to the rear of the governor’s grounds. He sends me a photograph of a lovely pond down by the governor’s back fence. Could it be one of Oxley’s ponds, still there because it has been, for more than a century, untouched and protected inside the fences of the regal property?21

I first read these words, along with other parts of Condon’s Brisbane, sometime in the middle of 2011, and undoubtedly they helped to sew the seeds for this website. By the time I came to writing this essay, I had completely forgotten the details of David’s theory, and upon revisiting them I was delighted to discover the parallels with my own conclusions. Of course, those parallels might not have been entirely coincidental. In fact, I probably owe more to David’s endeavours than I have remembered, as much of this website covers essentially the same ground, quite literally, that David had already charted. As Condon writes:

David goes even further. Now he’s concentrating on the ‘fine valley’ that Oxley observed. … A couple of weeks later he emails me a map. He believes he has ascertained the valley. He has tracked what he believes are the headwaters of the stream and its chain of ponds. He has discovered untouched and overgrown gullies deep in the heart of this patch of inner-city suburbia.

His map of the valley has at its southern border the ridge line that runs along the edge of the Toowong Cemetery and Birdwood Terrace. The ridge curves north through Bardon, and its northern extremity is formed by present-day Latrobe Terrace.22

The ridges that Condon describes in David’s map are precisely those on my own map of the Western Creek catchment. The overgrown gullies that David discovered are the channels running through in what I call the Weedy Wonderland, and they indeed form the headwaters of Western Creek. A network of drains now conveys water from these channels and other upper parts of the catchment to the governor’s property, and from there through to Gregory Park, Frew Park and Milton Drain. In Oxley’s time there would have been a creek running all the way through. Is this then the source of the chain of ponds?

Spring theory

Western Creek drains a sizable catchment area, but unless decent rain has fallen, you will rarely find more than a trickle left in Milton Drain once the tide drops. If there were no concrete drains to carry the water away, it would have a chance to form ponds; but in dry periods even these ponds would not last very long if fed by runoff alone. To draw any conclusions about the source of Oxley’s chain of ponds, we need to consider something that has been missing from this analysis so far — the weather.

What had the weather been like when Oxley visited in September 1824? Thankfully, Oxely’s field book contains much of what we need to know. On Wednesday 22 September, Describing the region near Mount Crosby, where the depleted state of river impeded any further progress upstream, Oxley noted:

The whole country bears the marks of extreme drought, and I should think it must have been many months since rains have fallen, at least of any consequence.

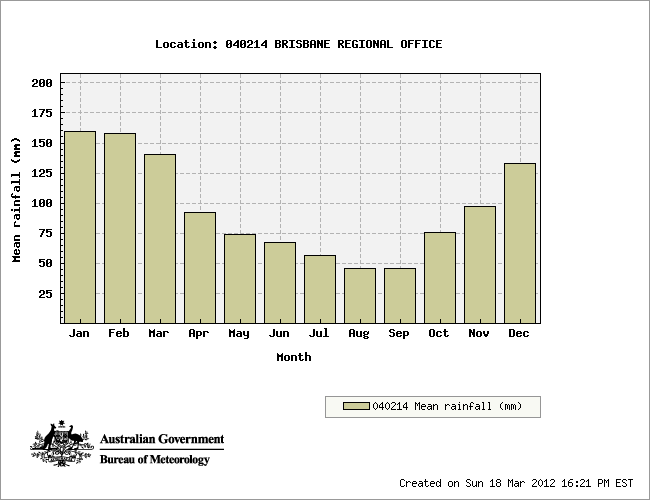

Of the river itself, Oxley noted on Monday 27 September: “when I first visited it in December, 1823, the water was found fresh about sixteen miles lower than we at present experienced it.” This and other references in Oxley’s field book make clear that the region was in drought. And on top of this, his visit coincided with what is typically the driest part of the year in Brisbane, as can be seen from this chart of monthly mean rainfall.23

So we can assume that in the weeks (probably months) leading up to Oxley’s visit, there had been virtually no rain, and that the Western Creek catchment would have been parched. But even a severe drought may be punctuated by the occasional fall of rain that brings temporary relief to the landscape. We therefore need to consider the day-to-day weather during Oxley’s visit, not just the seasonal tremds. Oxley recorded the weather nearly every morning in his field book, and occasionally commented about conditions later in the day as well. The sum total of his daily weather observations, starting from Thursday 16 September, is as follows:

- Thursday 16th (Redcliffe): “Fine, pleasant weather”

- Friday 17th (Breakfast Creek): no comment

- Saturday 18th (near Goodna): “In the evening we had a slight thunderstorm, with a light, refreshing rain”

- Sunday 19th (near Goodna): “A fine, pleasant morning”

- Monday 20th (three miles downstream from College’s Crossing): “The fogs and dews intensely heavy, but are soon dissipated by the strength of the morning sun”

- Tuesday 21st (near Mount Crosby): “A fine, clear morning”

- Wednesday 22nd (near Mount Crosby): “The weather continues very warm and sultry”

- Thursday 23rd (near Mount Crosby): “Fine and clear”

- Friday 24th (near Mount Crosby): “The weather continues very hot and sultry”

- Saturday 25th (near Mount Crosby): “Clear and sultry”

- Sunday 26th (near Goodna): “Hot, sultry”. “During the evening we had a severe storm of thunder, lightning and rain”

- Monday 27th (near Goodna): “Sultry as usual”

- Tuesday 28th (Auchenflower): “A calm, still night”

Over all, the weather appears to have been warm, dry and sultry, almost monotonously so. Only twice does Oxley record a deviation. On the 18th, there was a “slight thunderstorm” and some light rain. Then on the evening of the 26th, two days before Oxley discovered the chain of ponds, there was a much heavier storm. Cunningham also recorded this event in characteristically more verbose terms:

Upon proceeding down the River however about 2 miles, heavy clouds were perceived gathering from the Northward, indication of an approaching storm, it was therefore deemed advisable to land and encamp,24 and the tents had scarcely been pitched an hour, before the Thunderstorm in its passage over us to the Southward, drenched us with a copious rain which proved most serviceable to the parched lands around us that had apparently not imbibed much moisture from the clouds for many weeks.25

Did the storm that passed south over Goodna hit the Crescent Reach as well? Could it have dumped enough rain to leave substantial ponds in Western Creek two days later? Given how dry the catchment must have been, I suspect that any rain that did fall would have been quickly soaked up by the thirsty ground. Remember that Oxley searched for water at Langsville creek on the evening of the 27th (the day after the storm) but failed to find any, suggesting either that the rain had already drained away or that there was little of it in the first place. And even if the storm had replenished the waterholes of Western Creek, surely Oxley would have recognised this as an isolated event when reporting a reliable source of fresh water. Indeed, what else could he have have been thinking when he wrote about the water “being at this season a chain of ponds”?

When I first read about Oxley’s chain of ponds in Matthew Condon’s Brisbane, I assumed that the words “at this season” referred to a wet period that had left the catchment saturated and flush with life. But the above analysis of Oxley’s field book reveals the exact opposite: Oxley was referring to a dry season, and not only that, a severe drought. What, then, was the source of the abundant fresh water that he found in the chain of ponds?

The only answer that I can offer is that the water came from underground. Just like the creek at Roma Street that was dammed to supply the fledgling settlement, the ponds of Western Creek may have had their source in a spring — a surface expression of an underground body of water. Underground water, or groundwater, ultimately comes from the same place as surface water — that is, rain. But groundwater moves more slowly and collects in much greater volumes than water at the surface, making it invaluable in times of drought or in places where surface water is hard to find.

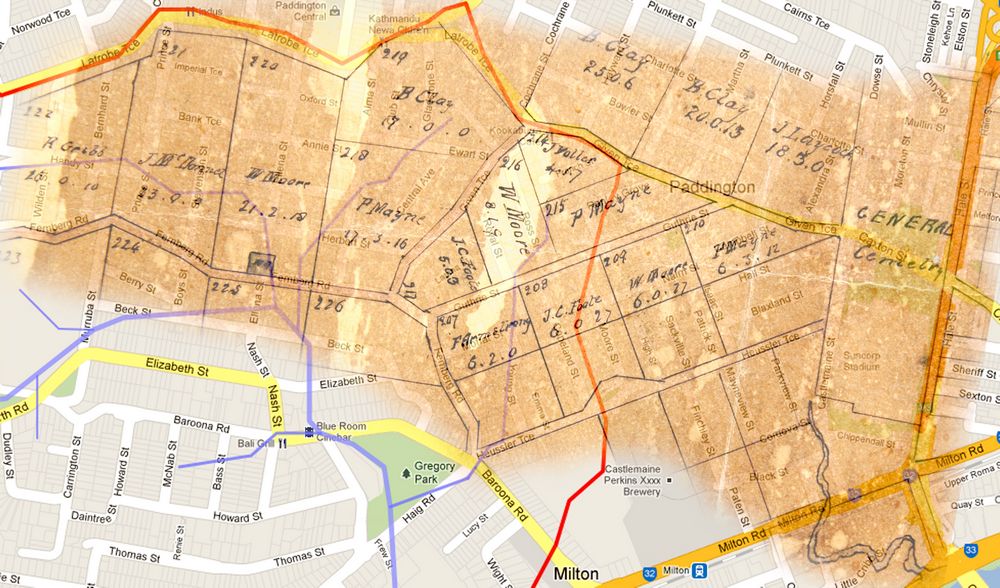

I have found one tantalising clue that there was indeed a spring in this part of Western Creek. In 1864, a petition was sent to the Secretary for Land and Works by J. C. Heussler, who was one of the early residents in the area and the first owner of Fernberg, which later became Government House. The petition was signed by local land owners, residents and farmers, and humbly begged “that a Water Reserve may be formed at the Red Jacket Swamp26 . . . where there is a spring of the purest water upon which the inhabitants (some hundreds, and daily increasing) have been entirely dependent during the late drought”.27 A map included with the petition shows the location of the spring to be at the intersection of Fernberg Road and Ellena Street. The figure below shows part of this map superimposed on a modern-day street map. Also shown is the approximate path of Western Creek and its tributaries, derived from digital elevation data.

A map accompanying an 1864 petition overlaid on Google Maps. The proposed water reserve can be seen on Fernberg Road, to the left of the picture. (The original map is held at the Queensland State Archives, ID22054)

Sinking a water bore at the Castlemaine Brewery, Milton, Brisbane in 1895 (John Oxley Library, State Library of Queensland, Neg: 94888)

This “constant spring . . . available at all seasons”28 could have fed a chain of ponds stretching all the way from Fernberg Road to Gregory Park. And who is to say that there weren’t other springs in the area? In fact it seems quite probable that a spring feeds the pond at the bottom of Norman Buchan Park and Government House. This pond, which apparently did not dry up even in the Millennium Drought29 does not appear to be fed by the drain, which seems to pass around or underneath the pond. This all suggests that the pond is fed by groundwater.

I’d love to be able to say more, but I don’t know anything about the groundwater systems in this area, and I have no idea who does. I don’t know of any wells being dug or bores being drilled in the area at any time (though there will soon be a great big tunnel30 bored right under Rosalie Village). The closest thing I have found is a picture held by the John Oxley Library purportedly showing a water bore being sunk at the Castlemaine brewery in 1895. Accompanying the photograph was the following text:

Altitude 617 ft. Depth 600 ft. Yield per 24 hours 3,000,000 gallons. Pressure per square inch 185 lb. Temperature 115 degrees Fah. Boring machinery bore abandoned.

The last two words suggest that the enterprise wasn’t very successful, despite the huge volume of water that was apparently tapped. Perhaps the quality of the water was poor on account of it being so close to the river. Whatever the case, it is a reminder that there is more water in the landscape than just what we can see.

The source of the water aside, the presence of the pond at Government House still presents something of a mystery. Why was it not filled in like the rest of the creek? Perhaps it was filled in, but remained so boggy that it was returned to being a pond. At some point I hope to do some research and find out. If this roadside waterhole really is one of the links in Oxley’s chain of ponds, then it should be treasured as a small miracle.

The creek through the ponds

We Australians are not known for taking a strong interest in our own history. Whether this is because we are embarrassed, ashamed or just plain bored by it, I don’t know. Clearly though, this national trait also holds true for the city of Brisbane. How else could we have tolerated a misplaced foundation stone that not only stood uncorrected for sixty years, but that has continued to stand despite being corrected for over twenty years more?

We could do well to show a little more interest in our own origins, and to pay a little more attention to detail in doing so. At the same time though, a preoccupation with historical detail can be taken too far. We should never get too hung up on identifying exactly where Oxley landed, or which valley and which chain of ponds he encountered. For one thing, we simply don’t have enough information to do find out. Despite the dot-joining exercise above, and the similar efforts by T.C. Truman, David Barr and others, I don’t think anyone can say with absolute confidence where Oxley really came ashore and discovered water on the 28th of September 1824.

And nor do we need to, for ultimately these sorts of details are not what matter. Yes, we can get a kick from knowing that we are standing in the very place where so-and-so discovered such-and-such; but as ever, we should be careful not to miss the forest of the trees — or in our case, the creek for the ponds. By considering what John Oxley’s observations mean for Western Creek, rather than just what the ponds and the valley meant for John Oxley, I hope to have drawn attention to some features of this suburban landscape that might otherwise go unnoticed or be forgotten. The creeks of the Crescent Reach, for example, though now largely covered or buried are in a sense still with us, having left their mark in the fine valleys that give shape to our parks and streets.

There are creeks underground too, moving slowly, silently and invisibly except where they have found expression as streams, swamps, and ponds. These features have also been largely swallowed up, but here and there you might find one that has seeped through the cracks of the urban cover — like the little pond at the back fence of Government House. For all the fuss made (or not made) about the stones at North Quay and Milton, perhaps this pond is really the monument we should care about. As grand as they are, the stones are mere artifacts bearing no real connection to the event they commemorate. The pond, on the other hand, might just be a relic from the event itself — a direct link Brisbane’s foundation, and to the Western Creek of old.

Or maybe not. Who knows? Either way, it’s worth giving some thought next time you get the chance to gaze over the Governor’s back fence.

Notes:

- Apparently no record has survived of the unveiling of this monument (Matthew Condon (2010), Brisbane, University of NSW Press: Sydney, p268). ↩

- Condon, Matthew (2010), Brisbane, University of NSW Press: Sydney. ↩

- Condon, Matthew (2010), Brisbane, University of NSW Press: Sydney. ↩

- T.C. Truman, The Courier Mail, 6 May 1950, p8. You can read this article on Trove. ↩

- Before the John Oxley Centre was redeveloped, there were plaques in the courtyard engraved with extracts from Oxley’s diary. ↩

- Oxley was not the first European to discover the Brisbane River. They honour belongs to three castaways — Thomas Pamphlet, John Finnegan and Richard Parsons — who were shipwrecked in Moreton Bay several months earlier. Pamphlet greeted Oxley upon his arrival at Bribie Island in November 1823, and a few days later Finnegan led Oxley to the Brisbane River. Meanwhile, Parsons was on his own, walking north in search of Sydney. ↩

- I have generally quoted Olxey’s field book from the transcription in J.G. Steele’s The Explorers of the Moreton Bay District 1770-1830 (University of Queensland Press, 1972), which is much easier than deciphering Oxley’s handwriting from the digital reproduction available on the State Library of New South Wales website. ↩

- While Oxley merely describes the journey to the bay as a “fatiguing row”, Cunningham’s diary of the same day notes that “The flood tide had made before we quitted our Encamping Ground. We had therefore to pull down against its influence until about 2 p.m. when we had it, together with an occasional puff of westerly breeze, in some of the Reaches in our favour.” (J.G. Steele (1972), The explorers of the Moreton Bay District 1770-1830, University of Queensland Press, St Lucia, Queensland.) ↩

- The Brisbane Courier, 14 June 1894, p2. ↩

- This creek became known as Wheat Creek, as for a time a wheat crop was cultivated there (Thom Blake (2004), Historical Overview: Roma Street Parkland Precinct, Queensland Department of Public Works, Brisbane. Available online at http://www.romastreetparkland.com/SiteCollectionDocuments/pdfs/rsp_history_e-book.pdf). ↩

- The Brisbane Courier, 29 September 1924, p7. ↩

- Pearn, John (1997), Auchenflower – the suburb and the name: A history of Auchenflower, Brisbane, Australia, Amphion Press: Herston, Qld, p15. ↩

- Pearn, op. cit., p17. ↩

- Truman, op. cit. Truman is non-committal about the location of the ponds, offering as another possibility the area “where the Brisbane City Council transport department and tramway depot are” — known today as the Coronation Drive Office Park. This is at odds with J.G. Steele’s statement in The Explorers of the Moreton Bay District 1770-1830 (p129) that “Truman has convincingly argued that the place referred to was Frew Park, Milton”. ↩

- The Brisbane Courier, 24 July 1896, p7. ↩

- If the bottom of the drain is deeper than the bottom of the natural channel, the tidal water would of course reach further than it would have naturally. I don’t know enough about drain construction to know whether this might be the case at Gregory Park and Baroona Road. ↩

- G.R.C. Mcleod, “A short history of the dredging of the Brisbane River, 1860 to 1910”. This document is available online, and appears to be a chapter of a book, but unfortunately I cannot tell which book this is. ↩

- Chapter 12 in the State of South-east Queensland Waterways Report 2001 states that “Historically, the Brisbane River contained upstream bars and shallows and had a natural tidal limit of only 16 km. The current tidal limit now extends 85 km upstream due to continual channel dredging” (p75). This suggests a dramatic change indeed, but unfortunately no explanation or reference for this claim is provided. ↩

- See this post for more discussion about the changing tides of the Brisbane River. ↩

- Various references can be found in The Brisbane Courier to a swamp in Rosalie. For example, a ratepayers meeting reported on 13 March 1886 (page 3) discussed the poor state of Beck Street (then called Mary Street) with one speaker noting that “some parts of it were literally in the swamp”. A hand-drawn map from Police Department files dated June 1886, reproduced in Alan Miles’ A history of the Rosalie Baptist Church 1884-1984 (1984), shows several streams converging around the intersection of Fernberg Road and Ellena Street, each labelled simply as “Swamp”. ↩

- Condon, op. cit., p271) ↩

- Condon, op. cit, p272-3. David: if you’re out there, I would love to hear from you!!! ↩

- This chart shows the averages for 1841-1994, the widest range available. Charts for more periods in the 19th century, such as 1861-1890, are not as ‘smooth’, but overall look very similar. ↩

- Steele notes that this was “On the right bank, below Cockatoo Island”. ↩

- Steele op. cit., p173. ↩

- At this time, the name “Red Jacket Swamp” was used to describe a broader area than just Gregory Park. See this page for more details. ↩

- Miles, Allan T. (1978), A history of Rosalie, Eastwood, NSW. ↩

- Miles, op. cit. ↩

- Pers. comm., Marci Webster-Mannison, January 2012. ↩

- For a time in 2011 there was what looked like a truck with a small drilling rig parked on Baroona Road near Bayswater Street, presumably surveying the subsurface to plan for construction of the Legacy Way tunnel. ↩

Last modified: September 2, 2023

Great essay Angus – really well written – I want to rush out now and see all these sites from a different perspective!

one thing to think about is the fact that the Aboriginal clan that lived in the

toowong area would not be there if there was no fresh water , they were called the Duke of York clan back then and also i have read of another camp of the Turrbul people being up where the present Woolworths is , they were never far from fresh water and lagoons for obvious reasons, another thing to think about at that time is the forests were a lot thicker as Government house area remains today so less evaporation from the sun, the ponds may have remained full.. the original tribes of people always travelled along pathways that followed watercourses and creeks and also their bora rings are always to be found close to fresh water, i am not sure but i have heard a rumour that there was a ring pretty much where the Regatta hotel is ..

A fascinating read from one who loves our Toowong Creek and often fantasises that we could get rid of the pipes and restore the whole creek! And wouldn’t Western Creek look better if it was not a drain!

More great research and writing work Angus

There is a well kept old historic colonial house in McDougall Milton St that was open as some sort of museum about ten years ago. (Next to the tennis courts) Built from memory about 1840. I has old photos and memorabilia on the wall dating from those early years.

excellent a pommie aussie

Hi Angus – great to revisit this page after seeing a prompt on Lost Brisbane. Keep up the great work. Peter

Conroy Smith Dutty Money https://commons.downhilltravel.co.uk/44.html Can Ergun Walking Around

r2dyig

4a7hlt

w7yc6o

0v680r

8m19la

5zaufy

xs0tr4

8wwuaf