In the fourth episode of Uncovering Langsville Creek, I told the story of Elizabeth Dale, who on 31 January 1905 drowned in a waterhole in the Toowong Cemetery. I was intrigued by the notion that there was once a waterhole in this otherwise dry and barren land, so I set about trying to determine its location. I failed dismally, but at least got some mileage out of reporting my misadventure. Thankfully, two readers took pity and provided me with some new leads. I am glad to report that having followed those leads, I can now reveal where Elizabeth drowned. I would only be more glad if no-one else had figured it all out before me.

A wild ghost chase

My first attempt to find the site of the waterhole was as optimistic as it was misguided. The only clue I had was that the waterhole was somewhere near the graves of Elizabeth’s husband and brother. Or at least, that was the inference I drew — incorrectly, it turns out — from statements given at the inquest into Elizabeth’s death saying that her body “was found off a pathway between her husband’s and brother’s graves” and that “the pool was about 20ft. from the pathway”. I assumed that the waterhole and Elizabeth’s husband’s and brother’s graves must have all been close to one another, and that I could deduce the location of the waterhole by finding the graves of a Dale and a Dodd (I didn’t even know their first names) in a low-lying part of the cemetery.

That mission was never likely to succeed. Many of the headstones in the low parts of the cemetery — especially those from the 19th century — were unreadable or missing altogether, and unless I spent all day looking, I was never going to check all of the readable ones anyhow. On the bright side, I had a pleasant afternoon and got some exercise. I felt a little foolish, however, when a reader named Ann Stephens pointed me to a much smarter way of finding graves in Brisbane: the City Council’s Grave Location Search, which enables you to find a grave by specifying the person’s name and the year they were buried. It’s kind of like a Yellow Pages for the deceased.

The newspaper reports about Elizabeth’s death do not mention her husband’s first name, but they do reveal when he died. They explain that Elizabeth was visiting the cemetery on 31 January 1905 to mark the eleventh anniversary of her husband’s death. (The anniversary was actually the following day, but Elizabeth was heading out to Wynnum for a few days, and so had to pay her respects a day early.) Two men named Dale were buried in the Toowong Cemetery in 1894. One of them, Thomas Dale, was buried on 2 February. He shares his grave with Elizabeth, who was buried on the same day eleven years later.

The location of Thomas’ grave is shown in the image below, which is taken straight from the council’s Grave Location Search. Hover your cursor over the image (or touch it on a mobile device) to see the location in more detail.

The grave of Thomas and Elizabeth Dale, shown on the City Councils’ Grave Location Search

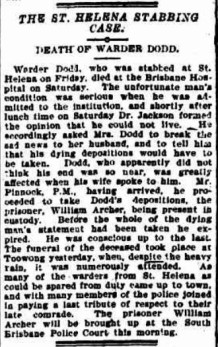

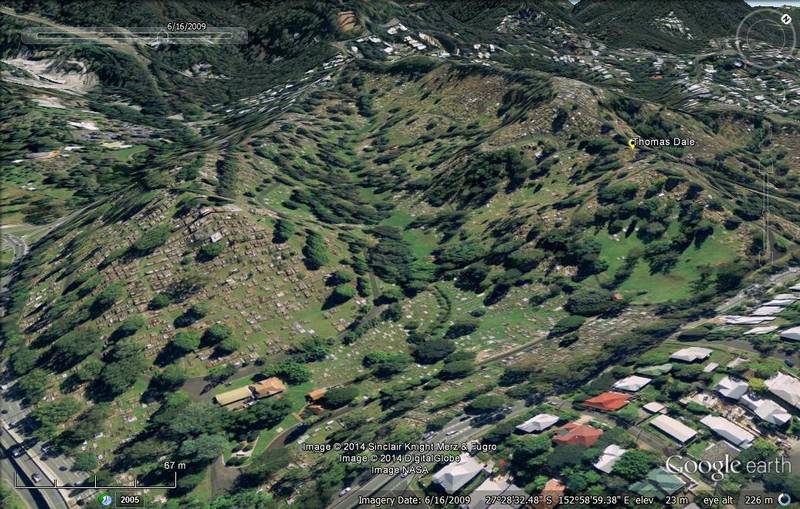

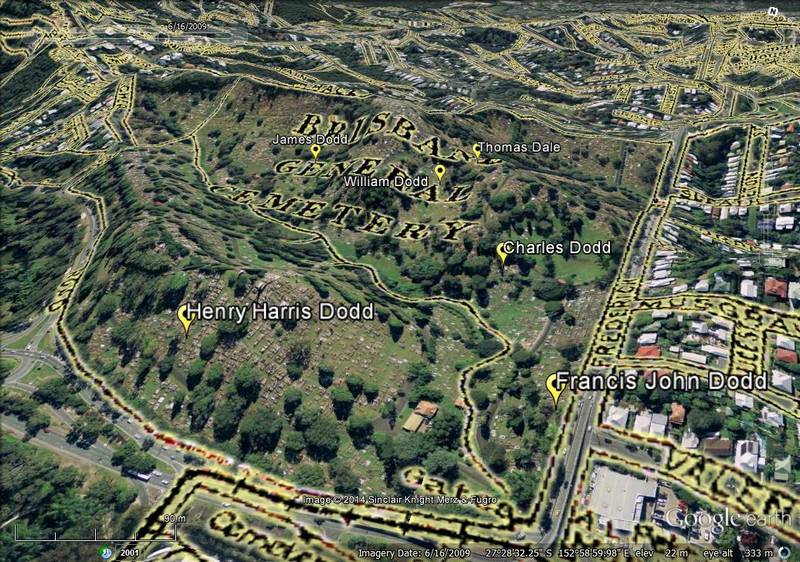

And here it is in Google Earth, with the terrain exaggerated to show where the grave sits within the slopes of the cemetery. Hovering over the image reveals a branch of Langsville Creek depicted on a map from 1929.

The grave of Thomas (and Elizabeth) Dale in the Toowong Cemetery, looking from above Frederick Street towards Mount Coot-tha. Hover over or tap the image to see an overlay of a map from 1929 depicting a branch of Langsville Creek. Note that the terrain has been exaggerated to show the slopes more clearly.

No wonder I didn’t find this grave during my first visit: it is not near a watercourse at all, but at the top of a hill. This meant that the waterhole had not been as close to Elizabeth’s husband’s grave as I had imagined. It also meant that her brother’s grave might not have been near the waterhole either — indeed, the two graves were likely to be a considerable distance apart given that the waterhole was situated somewhere between them. Elizabeth’s brother was therefore probably not William Dodd, who was buried in 1887 just a small distance down the hill from the Dales. Her brother was more likely one of the other four Dodds who were buried in the cemetery before 1905, and whose graves are marked on the image below.

The graves of Thomas and Elizabeth Dale and several Dodds, one of whom must be Elizabeth’s brother. Hover over or tap the image to see an overlay of a map from 1929 depicting a branch of Langsville Creek.

I’ll return to this matter a bit later, because I am making it out to be more of a mystery than it really is. To be sure, it was a mystery to me at the time. But I soon discovered that someone else had done a lot more homework on Elizabeth Dale than I had.

Time to dig deeper

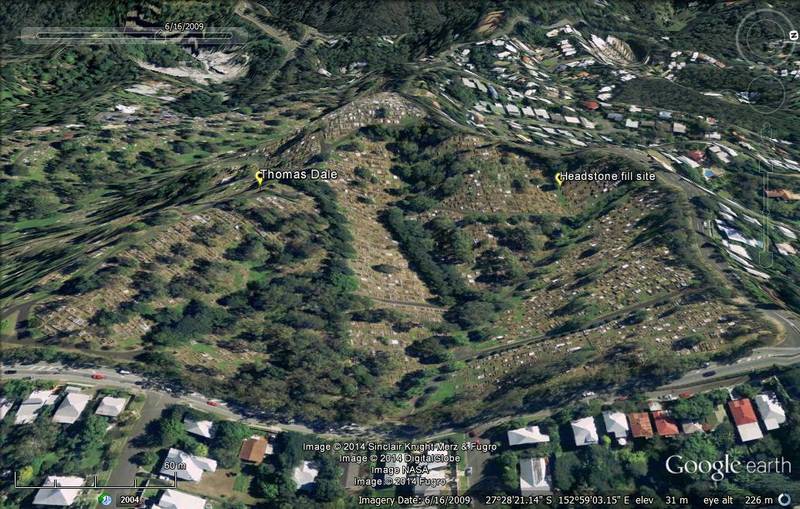

With my initial assumptions about the waterhole’s location now dead and buried, I needed a new lead. This lead came in the form of another reader’s comment, which mentioned that there was a depression in the Toowong Cemetery that had been filled up long ago with headstones from the old cemetery at Paddington (the cemetery was on the site where Suncorp Stadium is today). Could this depression have been the waterhole where Elizabeth drowned? I started poking around on Google, and discovered that the site is a regular focus of National Archaeology Week, held in the third week of May, in which a handful of experts and enthusiasts come together to excavate the old headstones. The dig site is a gully at the far northern end of the cemetery, as shown in the image below.1

This can’t have been where Elizabeth drowned. Aside from draining no more than a small gully, it is a long way from Thomas Dale’s grave, and is not located between his grave and any of the candidates for the grave of Elizabeth’s brother. This lead was starting to look like a dead end, but it was revived when my Googling turned up another page about National Archaeology Week. It was a post on the Archaeology Excavations blog about the 2010 National Archaeology Week event at the Toowong Cemetery. The post said:

In addition to the excavations the story of Elizabeth Dale, who drowned at the cemetery in 1905, will be retold and the graves of those involved in the story visited.

“The story of Elizabeth Dale . . . “. I could hardly believe what I was reading. But there was more. The post also linked to the following YouTube clip from 2007, in which Tam Smith of the University of Queensland describes an area cleared in the 1970s where various monuments were “bulldozed into the creek” (surely the place where gravestones go to die). She also talks about locating the site of the ‘Toowong Dam’, which was drained and filled in after Elizabeth Dale drowned in it.

Clearly, the story of Elizabeth Dale was well-trodden ground long before I stumbled across it. This meant that my own investigation was not the exclusive scoop that I had imagined, but on balance it was good news. Until this point I had been fumbling about in the dark: now, I had a way forward.

One thing that stuck out in the YouTube clip was the word Tam used to describe where Elizabeth drowned: she called it a dam — not, as the newspaper did, a waterhole. Suddenly things made more sense. I had struggled to believe that a sizable waterhole could occur naturally among the dry, steep slopes of the cemetery. But an artificial dam in the creek was entirely plausible.

The question, then, is where along the creek was the dam? Since learning the location of Thomas Dale’s grave, I had my eyes on one place: the area at the bottom of the hill, where there remains a fragment of the original creek flanked by a suspiciously flat clearing. In the first two Google Earth images above, this clearing stands out like the fairway of a golf course. My hunch that this was the location of the dam turned out to be correct. When I finally thought to look at the description of the cemetery in the Queensland Heritage Register, I found this:

From 1878, the Cemetery gardens were attended by dresser, William Melville, a position he held for 38 years. Flowers, shrubs and plants were cultivated on the site on Portion 10 and sold to meet the needs of the site’s visitors from a flower shed that straddled the creek. Mature camellias at the Cemetery, located in Portion 4 and 13 may be the first planted in Queensland from cuttings from Camden Park, the home of John McCarthur, who may have been the first to import them into Australia. A dam on Portion 16 was used for irrigation until 1905 when water taps were installed.

Portion 10, as shown on the official cemetery map, spans from the cemetery office near the main entrance to the bridge at 8th Avenue that separates the open concrete drain from the remaining part of the creek. Sometime around 1900, the flower shed was replaced with the sexton’s office, which is now the cemetery museum. Portion 16, where the dam was situated, covers the clearing on the northern side of the creek, shown in the photo below.

Portion 16 of the cemetery, where there is a remaining fragment of the old creek (Looking towards the south.)

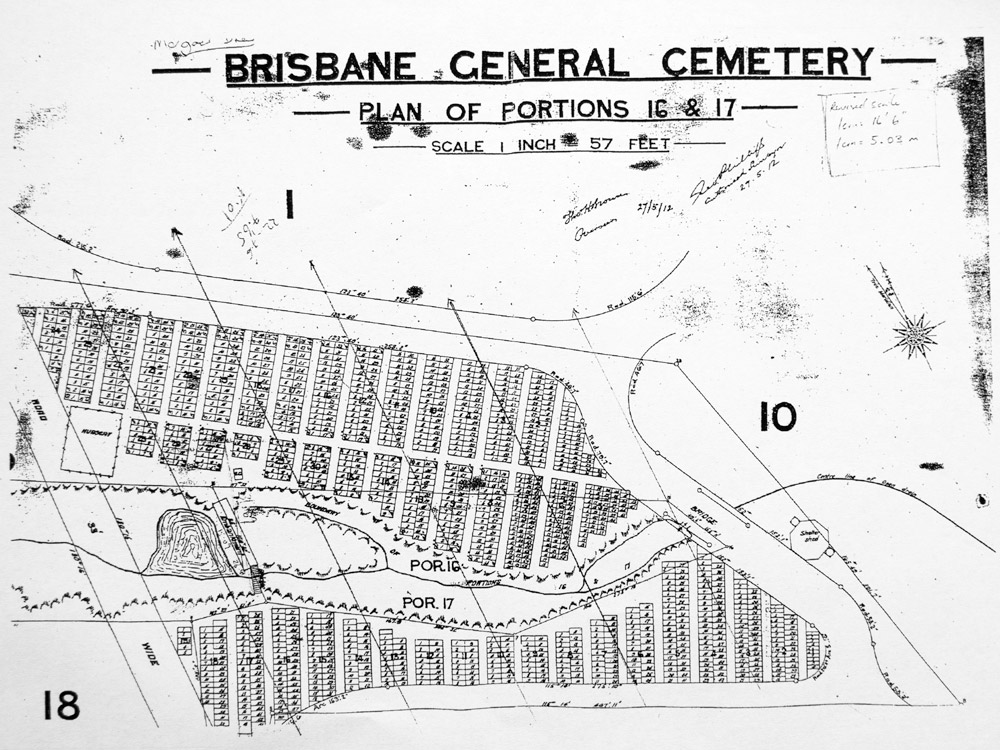

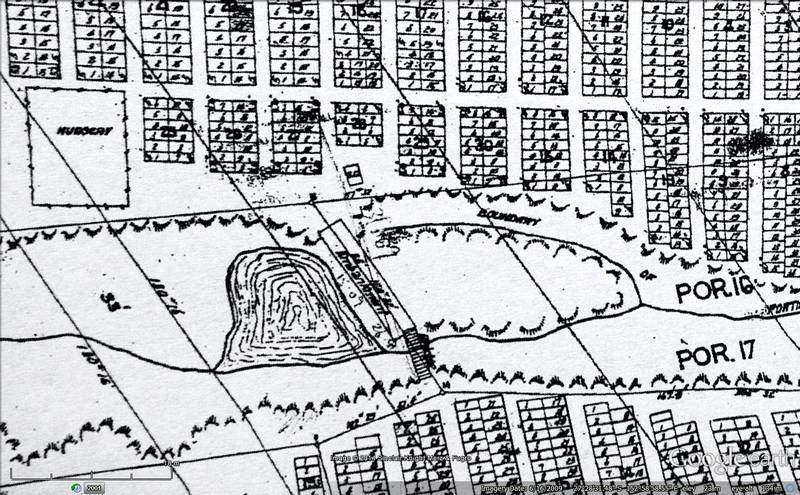

I decided at this point that it was time to stop bumbling about on my own. I got in touch with Tam Smith at the University of Queensland, and found that she was happy to share all she knew about Elizabeth Dale. She provided me with a collection of notes about Elizabeth’s case that had been prepared for National Archaeology Week activities back in 2007.2 From my point of view, the most exciting item among the notes was this plan, which was drawn before the dam was drained:

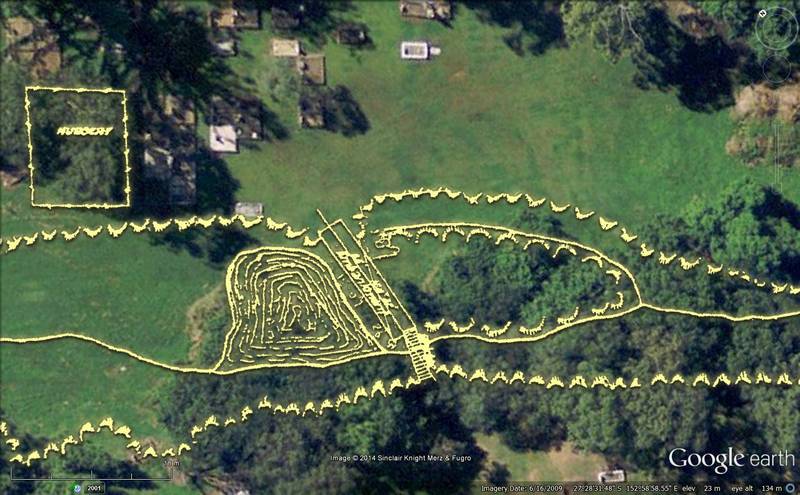

The plan covers portions 16 and 17 of the cemetery, which lay on either side of the remaining part of the creek. Here is what it would look like if it were blown up to a 1:1 scale and placed on the land it depicts:

The pre-1905 plan covers portions 16 and 17, which include the remaining fragment of the creek.

As well as depicting the dam, the plan shows plots for hundreds of graves on either side of creek, where only a few monuments remain today. There is probably an interesting story behind those monuments, but I only wanted to know about the creek and the dam, so I prepared a version of the plan with all the other details taken out.3 The result is shown in the two images below. Hover over an image (or touch it if you are using a mobile device) to see the original plan in the same position.

The pre-1905 plan shows that the dam was located at the upstream end of the remaining part of the creek in Portion 16.

These images reveal that the dam was at the upstream end of the remaining part of the creek. They also suggest that the dam, along with much of the creek channel, extended some way into what is now a flat lawn. In other words, not only the dam but also some of the creek itself has been filled in. This will come as no surprise to anyone who has seen the northern bank of the creek, which is composed largely of rubble:

The northern bank of the creek is full of rubble, suggesting that the land has been filled in. (Click to view a larger version.)

The dry creek bed, looking upstream towards the site of the dam. The bank on the left (south) is steeper and seems more natural than the one on the right (north), which is full of rubble.

Looking at the plan more closely, you can see the embankment of the dam as well as a small bridge over the creek. Also visible is the site of a nursery that presumably used water from the dam.

The pre-1905 plan covers portions 16 and 17, which include the remaining fragment of the creek.

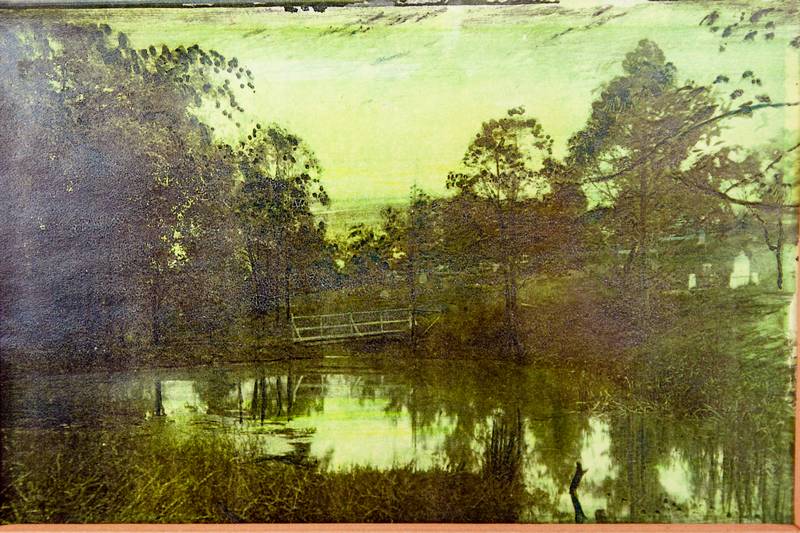

As well as the plan, Tam’s notes also contained a copy of the only known photograph of the dam. It supposedly came from the collection of the Royal Historical Society of Queensland, but the society seems not to know anything about it. I hope to track down the original eventually, but in the meantime, all I can offer is this photo of a photocopy:

A photo (of a photocopy of a photo) of the dam in the Toowong Cemetery, taken before the dam was drained in 1905.

A similar view is shown in this picture (I believe it is a photograph that has been hand-tinted) which hangs in the cemetery museum:

This hand-tinted photograph of the dam hangs in the Toowong Cemetery Museum (photographed by the author).

Both images show the view looking south from the northern corner of the dam towards the bridge and the embankment. The same view today is shown in the photo below. (For a wider view, see the photo presented earlier.)

Elizabeth’s final footsteps

When I started this investigation, I would have been happy just to deduce approximately where Elizabeth drowned. Now, thanks to the work of Tam Smith and her colleagues, I have a plan showing the precise location of the dam and a photograph showing what it looked like. I know more about where Elizabeth drowned than I ever anticipated. But there still remains the question of how she drowned. Was it an accident? Foul play? Perhaps even suicide? What can we conclude about her final footsteps?

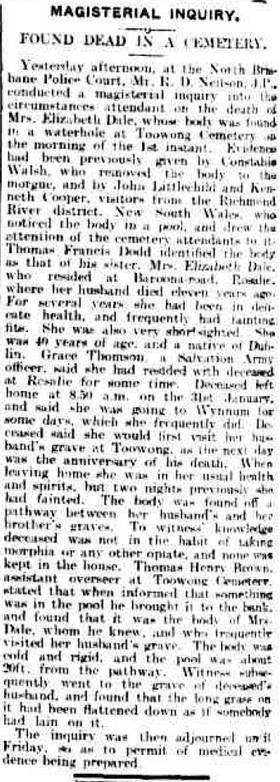

One of two reports in the Brisbane Courier about the inquest into Elizabeth Dale’s death. Whether the headline was supposed to be ironic is unclear.

The only evidence that we have to work with is what was presented at the inquest into Elizabeth’s death. The findings of this inquest, as reported in the Brisbane Courier, were what set me off on my initial misadventure through the cemetery. To recap: the coroner concluded that Elizabeth drowned, and that there was no evidence of foul play, although there was a small bruise beside her mouth. A trace of morphine was found in her stomach, but this was attributed to a cough medicine that she had been taking. The day she died, Elizabeth planned to visit the grave of her husband to mark the anniversary of his death. She also had a brother buried in the cemetery, and the inquest noted that her “body was found off a pathway between her husband’s and her brother’s graves”. Elizabeth had left home that morning “in her usual health and spirits”. For several years, however, “she had been in delicate health, and frequently had fainting fits. She was also very shortsighted.”

That much can be read in the newspaper. However, among Tam’s trove of notes was a copy of the full written record of the inquest, the original of which is held in the Queensland State Archives. The record includes testimonies from several witnesses, including the visitors who found Elizabeth’s body in the dam, the assistant overseer of the cemetery, the police constable, the medical examiner, Elizabeth’s brother and sister, and a friend who was staying at Elizabeth’s house the day she died. I hoped that these accounts might contain some clues that the newspaper had left out. Alas, they just describe the same facts in more detail.

There is one discrepancy, however, that is of some consequence if we wish to reconstruct Elizabeth’s final moments. It concerns the location of the dam with respect to her husband’s and brother’s graves and the pathway running between them. The Brisbane Courier reported that “the pool was about 20 ft. from the pathway”. This led me to assume (once I knew where the dam was located) that the pathway in question was one of the roads running parallel to the creek (either 8th Avenue or 14th Avenue on the official map), which in turn would have implied that Elizabeth went out of her way to go to the dam. But what the assistant overseer actually said was: “I saw an object in the water and what looked like the crown of some person’s head and about 20ft from the pathway and bank”. So the pathway and the bank were the same thing. What the overseer was referring to was the embankment of the dam, which is visible in the plan and in the photographs shown earlier. He saw Elizabeth’s body floating about 20ft upstream of the embankment.

At the inquiry, Elizabeth’s friend, Grace Thomson, said that the place where Elizabeth’s body was found “is on a pathway from her husband’s grave to her brother’s grave”. Elizabeth’s other brother, Thomas Francis Dodd, described the spot as being “in a direct line between her husband’s and her brother’s graves”. The implication is that Elizabeth passed by the dam on her way from one grave to the other. Let’s return, then, to the question of where her brother’s grave was located.

Henry Dodd and the cruel hand of fate

Earlier, I presented a picture showing the locations of the graves of Thomas Dale (Elizabeth’s husband) and all of the Dodds who, in the absence of any other information, were candidates for being Elizabeth’s brother. Given the location of the dam and the comments made at the inquest by Grace Thomson and Thomas Dodd, we can deduce that the brother buried in the cemetery is Henry Harris Dodd, whose grave is located at the southern end of the grounds on the slope overlooking Mount Coot-tha Road. If you were to draw a straight line between Henry’s grave and that of Thomas Dale, the dam would indeed be right in the middle. (Of course, you could also just identify Elizabeth’s brother in the registry of births, deaths and marriages, but where would be the fun in that?)

With the locations of the two graves and the waterhole now accounted for, we could pack up at this point and go home. We know where Elizabeth drowned, and we can guess at the course of her last earthly journey.4 Presumably, she was on her way from Thomas’ grave to Henry’s, but for some reason or another she got no further than than dam that laid between them. Or perhaps the dam was her final objective after all — we’ll never know. But since we have come all this way, we might as well see what more we can learn about Elizabeth, Thomas and Henry. A logical place to start is with their graves, which we still know only as markers on a Google Earth screenshot. We’ll have to get much closer to them if we really want to trace Elizabeth’s final footsteps. Since we’ve just located Henry’s grave, let’s look at it first.

I’m not sure why, but by this stage of my investigation I had formed the assumption that Elizabeth was from a family of modest means, and that both her gravestone and Henry’s would be of similarly modest proportions. I was therefore surprised to find that Henry’s gravestone stands taller than many of those around it. When I read the inscription on the grave, however, I discovered that Henry’s burial was more than just a family affair:

Erected by the officers of the Prisons Department in memory of their late comrade Henry H. Dodd, who was killed by a prisoner at St Helena while in the execution of his duty. 19th February 1898, Aged 31 years, and 6 months.

(On the northern face of the monument is a memorial to Henry’s daughter Elsie Gerletti, who died from convulsions two years earlier, aged just two years and four months. Henry and his wife — also named Elizabeth — had a second daughter, named Mureil, who was four months old when Henry died.)

As the inscription on his grave suggests, Henry was a prison warder at St Helena. On the afternoon of 18 February 1898, his duties brought him to the tailors’ workshop to relieve another warder named William James Downie, who had gone to the toilet. Without warning, a prisoner named William Archer stabbed Henry in the stomach with a saddler’s knife. Henry was treated at the Brisbane Hospital that evening, but by the following afternoon the doctor had “formed the opinion that he could not live”.

He accordingly asked Mrs. Dodd to break the sad news to her husband, and to tell him that his dying depositions would have to be taken. Dodd, who apparently did not think his end was so near, was greatly affected when his wife spoke to him.5

Henry died before completing his deposition, but not before identifying William Archer, who was present in the room with the police constable.6 Archer was charged immediately with Dodd’s murder, but he did not live long enough to stand trial. He was found dead in his cell at the Boggo Road Gaol on the morning of the 8th of May 1898.

William Archer had been serving a ten-year sentence for stealing materials from a tailor’s shop at Petrie’s Bight (a charge which he categorically denied7). An article in The Queenslander reporting on Henry’s death noted that Archer “has the reputation of at times being extremely troublesome”, and described him as “a man of pale, cadaverous appearance, about 37 years of age, and evidently suffering from consumption”.8 During his confinement at Boggo Road, Archer’s health deteriorated even further. Curiously though, the medical examiner concluded that Archer did not die from his “old-standing diseases”, but that “The cause of death was due to paralysis of the heart”. This vague, almost circular diagnosis suggests that the authorities did not really want to know what — or perhaps who — killed William Archer. There would have been no shortage of warders at Boggo Road who saw tuberculosis, or even the hangman’s rope, as too kind an end for someone who had murdered one of their own. Whatever caused Archer’s death, it seems fair to say that he had it coming.

Henry Dodd’s death as reported in the Brisbane Courier.

Henry Dodd, on the other hand, appears to have done little, if anything, to incite Archer’s attack. In fact, the accounts of several witnesses suggest that Henry wasn’t even Archer’s intended target.9 Moments after Henry was stabbed, Warder Downie rushed into the workshop, having heard the commotion while on the toilet. From the other side of an iron gate, Archer said to Downie, “You’re the —— I intended it for”. Archer then hurled the bloodied saddler’s knife at Downie. When the knife missed, Archer found and threw another knife, but struck only the bars of the gate. After the gate was opened, Archer brandished a pair of scissors and threw those at Downie as well. Downie dodged the scissors and leaped over a table to bring Archer under control, but not before Archer took a swipe at him with an iron pot. Later on, while Archer was waiting at the Jetty to be deported to Brisbane, he confided to the warder in charge, “I am sorry Warder Dodd got it; I intended it for another warder”.

I can’t help but imagine this detail playing on Elizabeth’s mind whenever she stood at Henry’s grave. Losing her brother to such a senseless crime must have been hard enough, but knowing that Henry’s fate had been intended for someone else can only have made it worse. Of course, William Downie might have been no more deserving of Archer’s knife than Henry — on this matter, the court hearings tell us nothing. But Elizabeth, a childless widow who had buried her husband only four years earlier, could have been forgiven for feeling that fate had dealt her a cruel hand.

William Downie and the toilet break of destiny

William Downie, meanwhile, must have been counting his lucky stars. But for a fortuitous toilet break, he would probably be dead, while Henry would still be alive. We can’t know how heavily this fact weighed on William’s conscience. But at the very least, he would have known that while he and Henry were of the same age and at the same stage in their careers, Henry left behind a widow (albeit one who remarried a year later10) and an infant child, whereas William himself was still a bachelor. William’s lucky break had, in a sense, come at a considerable human cost that would not have been incurred had things been the other way around.

For what it is worth, William Downie went on to enjoy a long life and a successful career — a career which, if anything, appears to have benefited from the incident at St Helena. When William retired in 1935 as the superintendent at Stewart’s Creek Prison in Townsville, the Townsville Daily Bulletin noted that “at one time in his career, he was granted a number of years’ seniority for an act of bravery whilst serving at H.M. Penal Establishment at St. Helena.” William remained at St Helena until he was transferred to the prison at Cairns in 1907, apparently much to the regret of his fellow officers at St Helena. He took up the post at Townsville in 1925.

Given that William Downie had been the intended object of William Archer’s aggression, we might wonder if he had a knack for ruffling prisoners’ feathers. But in spite of the incident at St Helena — or who knows, perhaps even because of it — Downie in his later career earned a reputation for fairness, gaining respect from both the officers and prisoners serving under him. When his retirement at Stewart’s Creek was immanent, the inmates sought help from the prison’s chaplain to present a memento on their behalf.

Father McCoy entered whole-heartedly into the scheme, and supplied the materials for a writing table, the result being a beautiful inlaid folding table manufactured by a prisoner in the prison. A man who had served a sentence under Mr. Downie, sent a silver desk set, mounted in glass to go with the table.11

The inmates gathered in a hall to present the gifts, and in the absence of Father McCoy, one of them read a gushing tribute to Downie’s service. Of course, how much of the prisoners’ gratitude was genuine and how much was expressed out of self-interest is hard to tell. In any case, Downie gave his thanks and said in reply that he “had always endeavoured to be just, and see things from their point of view”. The prison warders were also sorry to see William go. They presented him with an eight-day clock as a parting gift, and expressed “regret at having to part with a courteous, efficient and just superior officer”.

William Downie married his first wife, Julia Charlotte Smith,12 in 1901. She gave birth to a son in 1904, but the child died the same year.13 Julia had no more children of her own: she died in 1935, leaving only a foster daughter.14 The following year, William, who was then approaching 70, married Lorna Jean Warren, who was just 29. After their union was “quietly solemnised” in Townsville, the recent retiree and his young bride headed off “to Adelaide and other southern ports, on an extended holiday”.15 William Downie died in Townsville in 1952 at the age of 85, survived by Lorna, two sisters, and a daughter named Celestine.16

Elizabeth Dale never learned about the successes of William Downie, who was still just a warder at St Helena when she died in 1905. By that time, her brother Henry had been dead for seven years, but it seems likely that he was in her thoughts right up until the end. Indeed, the end might have come as she was walking towards his grave. Weighing even more heavily on her mind in those final moments, however, would have been the memory of her husband, whose grave she had just visited.

Somehow, we’ve come this far in the story without learning anything about Thomas Dale or the grave that Elizabeth came to share with him. So it’s time now for us to leave Henry Dodd alone and trek across the cemetery to the grave of Thomas and Elizabeth Dale.

Thomas Dale: another life cut short

If you paid any attention earlier to the picture of Henry’s gravestone, then Thomas Dale’s grave should look familiar. It is not as tall or majestic as Henry’s, but otherwise it looks much the same. The design that they share is that of a broken column, a symbol of a life cut short. In Thomas’ case, the column is not only broken but also leaning rather precariously. Otherwise it has weathered fairly well — except, unfortunately, on the side bearing his epitaph. With some difficulty, you can just make out the first four lines:

In loving memory of Thomas Dale

Who departed this life February 1st 1894

Aged 32 years & 9 months

His end was peace17

As discussed earlier, Henry Dodd’s life was cut short by what could be described as an occupational hazard. Thomas died of heart disease.18 He worked as a carpenter19 and lived with Elizabeth in a cottage on Baroona Road, about three doors up from Beck Street as you head towards Rosalie Village.

Inscribed beneath the first four lines of Thomas’ epitaph are four more lines of smaller, cursive text. The stone around these lines has weathered so much that I could not read them with the naked eye. Even after taking a picture and Photoshopping it beyond recognition, I could not make out the words. I had to resort to more primitive technology and take rubbings with a pencil and paper.20 Not having done a pencil rubbing since I was about eight, I didn’t do a very good job, so I am still not sure about all of the words, but they resemble the following:

Far beyond this world of sorrow

Far beyond this world of care

I shall find my missing loved one

In my Father’s mansion21

On the foot of the gravestone are the words: “Erected by his widow, Elizabeth Dale”. This much, at least, we might have guessed. Elizabeth had been married to Thomas for six years, and after he died she never let him out of her life. She visited his grave frequently, right up until the day she died. She also remained at the same cottage in Baroona Road where she and Thomas had lived since 1891.

In Elizabeth’s day, a widow was expected to mourn her husband for at least two years, and in some circles up to four years. Interestingly, on the fourth anniversary of Thomas’ death, Elizabeth had a memorial to him printed in the newspaper. Perhaps this memorial was supposed to mark an end to Elizabeth’s grief, a point at which she could break from the past and move on with her life — perhaps even remarry. Sadly though, she was not released from mourning for long. Just three weeks after the memorial was printed, her brother Henry was fatally stabbed at St Helena.

We know only a handful of facts about Elizabeth’s life, but it is hard to assemble them into anything other than a picture of recurring tragedy, at least from the death of her husband onwards. We can hardly blame her if she wanted to leave behind her world of sorrow in order to be with her missing loved ones. On 31 January 1905, she did just this, departing by way of the dam that laid between the graves of her beloved husband and brother (and, as we will see shortly, her parents as well). She was laid to rest with Thomas two days later. Her epitaph, which is inscribed on the northern face of the headstone, reads:

Elizabeth

beloved wife of

Thomas Dale,

Died Feb. 1st 1905

Aged 40 years.

Thy will be done

Whoever commissioned this epitaph assumed some poetic licence with regard to the date of Elizabeth’s death. Although Elizabeth’s body was not discovered until 1 February, the certificate from the inquest confirms that she died on 31 January. To honour that detail, however, would be to forsake the more symbolically powerful notion that Elizabeth died on the exact anniversary of her husband’s death. United in this way, two deaths seem less like the results of blind, merciless chance and more like the ordained parts of some higher plan — an interpretation that is reinforced by the presence of the fourth line of the Lord’s Prayer at the end of the epitaph.

But I can’t help reading that final line in another way. Might Elizabeth’s poetic end have been the doing not so much of God’s will as of her own? Suicide is certainly a plausible theory, but the evidence from the inquest also admits other possibilities. Both Thomas Dodd and Grace Thompson said that Elizabeth was in delicate health, was very short-sighted, and was prone to fainting. The medical examiner noted a slight bruise on her cheek, which “may have been caused by a fall”. Might Elizabeth have fainted and fallen as she walked along the embankment of the dam? Or slipped first and fainted or knocked herself out as she fell?

It’s also worth remembering that the dam in which Elizabeth drowned was at most five feet deep (the assistant overseer estimated five feet, while the police constable estimated only three to four feet). Perhaps Elizabeth was only five feet tall, but even so, I think it would take a considerable act of will to drown yourself when there is nothing to prevent you from coming up for air: you might as well do it by holding your breath.

Elizabeth’s triangle of tragedy: the dam in which she drowned is surrounded by the graves of her husband, brother, and parents.

There are still more threads to Elizabeth’s story that we could follow. Most notably, her parents are also buried in the Toowong Cemetery. In fact, their grave is even closer to the site of the dam than are the graves of Thomas and Henry. When you mark the three graves on the map, you get a triangle with the dam almost at the centre: the symbolism is almost too perfect to ignore. But ignore it I shall. My legs are tired, the sun is setting, and it really is time to pack up and go home. After my last post about the Langsville Creek, I more or less vowed not to do any more research into the cemetery stream, given that at my current rate of progress I may never wrap up my investigations of Western Creek, from which Langsville Creek was only ever meant to be a brief distraction. And yet, six thousand words later, here I am. Elizabeth’s story — tragic, ironic, and poetic in equal measure — proved too much for me to resist. I just hope I have done it some degree of justice. I hope also that I have done justice to the detective work of the Toowong Cemetery Archaeological Project team, to which this article is heavily indebted. Most of all, I hope I have been fair to the memories of those people whose names I have exhumed from the archives for the sake of nothing more (though hopefully nothing less) than a good yarn. Next time I wander through the cemetery, their ghosts might be watching.

Notes:

- This issue of the UQ Social Science Newsletter names the cemetery as the site of National Archaeology Week (NAW) activities in 2012 and 2013, while the NAW Facebook Group has the details for 2014. The 2012 dig is also mentioned in a comment to this excellent article about the Paddington Cemetery. ↩

- The Toowong Cemetery Archaeological Project was developed by Michael Haslam, Tam Smith and Jon Pragnell of the University of Queensland, with assistance from Hilda Maclean of the Friends of the Toowong Cemetery. ↩

- I should note that aligning this plan required a bit of guesswork, because it contains few features that can be matched to the present day. So the alignment might not be exactly right, but I am confident that it is pretty close. ↩

- There is in fact no path that will take you directly between Henry’s grave to Thomas’ graves. The most likely route to take, especially if you were in delicate health like Elizabeth, is actually quite circuitous, though it would have been made shorter by the bridge across the dam. Looking at the cemetery map, Thomas’ grave is in Portion 1 near 2nd Avenue, whereas Henry’s is in Portion 11, just down the hill from the Governor Blackall Memorial. The most direct route in Elizabeth’s day would have been to walk straight down the gentle hill in Portion 1, across the creek, up the hill in Portion 14 to Blackall’s memorial, and down the other side. If Elizabeth wanted to avoid the hill in Portion 14, she would have followed 8th avenue around to Boundary Road. ↩

- The Brisbane Courier, 21 February 1898. ↩

- The Brisbane Courier, 1 March 1898. ↩

- At the court hearing on 1 March 1898, Archer requested a solicitor, stating that he “was now serving ten years for an offence which it was well known he had nothing to do with. If he had not been able to get out of it in the last case, when he was entirely innocent of the charge, how much less could he get out of it now he was on trial for his life, unless he had legal assistance?” ↩

- Archer was in fact 40 years old. ↩

- The Brisbane Courier, 1 March 1898. ↩

- In 1899 Elizabeth married William Hood. She died in 1958, aged 90. ↩

- The Brisbane Courier, 5 July 1935. ↩

- Some records in the Queensland Register of births, deaths and marriages give her second name as Charlotta. ↩

- He may have even died at birth. The online search results from the Queensland Register of Births, Deaths and Marriages specify only the year of the events recorded. ↩

- The foster daughter may have been Gertrude E. M. Tilley, whose name appears next to William Downie’s in a public thank you notice following Julia’s death. ↩

- Townsville Daily Bulletin, 20 February 1936. ↩

- I am not sure if Celestine is the foster daughter mentioned in the report of Julia’s death, or a daughter of William and Lorna. ↩

- In case you are wondering, I could see no evidence of the letters ‘f-u-l’ at the end of the last word. But I will double-check next time I visit. ↩

- This information comes from the fact sheet prepared by Michael Haslam for the 2007 National Archaeology Week Toowong Cemetery Archaeological Project, which presumably consulted Thomas Dale’s death certificate ↩

- His occupation is mentioned in the post office directory and in his funeral notice. The 1889 directory lists Thomas at Elizabeth Street, on the right-hand side about five houses up from the junction with Nash Street. That directory lists him as a carpenter with the Railway department, though later directories just list him as a carpenter. From at least 1891 (I don’t have the 1890 directory), he is listed at Baroona Road. From at least 1900 (I don’t have the 1896-1899 editions) until 1905, the residence is listed as “Austin Dale cottage”. ↩

- There might be an even simpler way to read the inscription. If you were to catch the gravestone with the sunlight at just the right angle, the shadows within the letters might render them legible. ↩

- This is a variation on the second verse of the inscription on Elizabeth’s mother’s grave, which reads: When we leave this world of changes / When we leave this world of care / We shall find our missing loved one / In our Father’s mansion fair. Elizabeth’s mother is buried in the Toowong Cemetery in Portion 1, Section 44, Grave 6. ↩

Hahaha, ok, “Where’s the fun in that?” (verifying in BDM?…ENORMOUS fun, for me! Exactly what I did, when I read the first post re your ponderings on the then-unidentified Dodds and Dales!…sorry, should’ve read on/researched further before commenting…much as you should’ve, before setting off on your own research, only to discover the previous NAW Eliz. Dale research!)

My own great-grandfather (not a Dodd…or Dale…) is buried around there, along the edge of Mt Coot-tha Road, and now you’ve got me wondering if those Dodds are part of MY own Dodd family too!

Not bad research but some more info for you. The dam was not filled originally just the dam wall and foot bridge removed to let the creek flow as per pre-dam era after articulated water was provided. The dam area and the rest of the creek right back to near the Chinese section was filled with headstones and grave rubble between 1974 and 1979 and those were from many of the Portions in the cemetery not just the immediate area. Pioneers, soldiers & Judges were amongst the 2000 odd graves that were demolished in that period. The only headstones from the 7 North Brisbane Burials grounds were ones transferred mostly with remains to Toowong between 1875 and 1913 and some of those were amongst the ones destroyed in the authorised vandalism in those 5 years so are to be found in the old creek. Many headstones will never be recovered as the better condition ones were sold back to Masons to be recycled. A completely different area of Toowong was used in 1930 to hide some of the 500 odd headstones from the reserve near the site of the 7 North Brisbane Burial grounds. We have done 4 years of the digs on those and have recovered a good number in near perfect condition. Elizabeth did walk down 12th Avenue (now renamed Elizabeth Dale Walk) cross 8th Avenue (now Charles Heaphy VC) in that area almost directly through Portion 16 to the path over the dam wall and the short foot bridge over the overflow section up the pathway between Portions 12 and 14 and a short distance down into Portion 11 to her brother’s grave. Because the creek was an active flowing one to the dam and still taking the overflow as well it would have been an extremely long walk around in either direction. In that heavy long black mourning dress on a normally very warm late January day I feel she would most likely have paused to splash a little water on her face and this time either fainted or slipped. In that dress she would not have had a chance of getting out unaided. We know the exact location of the dam wall and footbridge and in fact that exact site was one of the two dig sites for this year’s excavation. We recovered 3 perfect headstones which will go back on the graves they were stolen from.

Wow, thanks for all that great info, Darcy!