This post is all about the part of Milton bounded by the railway, Cribb Street, Coronation Drive and Boomerang Street. If you live in Brisbane, it’s a place that you have probably passed many times without really noticing. From Coronation Drive it presents as a row of office buildings and some Jacarandas; from the train, as a car park and some Moreton Bay figs. From within, the site feels like a secluded, shady village. Interspersed with the eight office buildings and fig trees are a tennis court, a childcare centre, a multi-level carpark, an open carpark, cafes, and various shops including a Flight Centre and a real estate office. This site is known (to those who know it as anything at all) as the Coronation Drive Office Park.

The Coronation Drive Office Park covers 4.5 hectares and is bounded by Cribb Street, the railway line, Boomerang Street and Coronation Drive.

AMP Capital, which manages of the majority of the site,1 are considering the next stage of its development. Before commencing this development, AMP Capital wanted to learn more about the site’s past. They asked me if I would like to do some research, and I jumped at the opportunity. After several weeks plumbing the depths of Trove, the Brisbane City Archives and various other sources, I produced a report documenting the history of the Coronation Drive Office Park.

You can download the report here (it’s about 13MB — apologies for the big download), but for a shorter, more web-friendly version of the story, read on below. The story is divided into eight sections, each examining different phases or aspects of the site’s history: Before European settlement, The edge of town, A place of residence, Roads and railway, Boundary Creek, A site of industry, A hub of sanitation, and A hub of transportation.

Before European settlement

Most of what is known about the site of the Coronation Drive Office Park (from here onwards called the CDOP site) prior to European arrival comes from the records of the first European explorers and settlers. Captain Cook sailed around Moreton Bay in 1770, and Matthew Flinders surveyed part of it in 1789, but neither of them found the Brisbane River, let alone came close to the CDOP site — and neither did any other Europeans until 1823.

The accidental tourists

The first Europeans to discover the Brisbane River were not explorers, and they did not come there on purpose. They didn’t even know where they were. They were so thoroughly lost that they thought they were in Jervis bay, south of Sydney. These accidental explorers were three paroled convicts named Thomas Pamphlet, Richard Parsons and John Finnegan, who had set off from Sydney on 21 March 1823 bound for Illawarra. Their boat was blown off-course by a storm, and after three thirsty, wretched weeks at sea (during which a fourth passenger, named John Thompson, died) they came aground at Moreton Island.2

Through the generosity of the local Indigenous people, the three men regained their health and spent the next six months trying to walk back to Sydney. They rowed to present-day Cleveland in a canoe and headed north (they were lost, remember) until they reached the Brisbane River. Unable to cross it, they trekked upstream as far as Oxley Creek, where they found a canoe. Here they crossed the river, but found the scrub on the other side too thick and rough to walk through. Back on the south side of the river, with one man paddling and the other two walking (the canoe was not big enough for the three of them), they returned to the bay and continued northwards. In their journey to this point, the three castaways would have passed the CDOP site twice.

Their journey north did not get any easier. Pamphlet made it is far as the Mooloolah River before aching feet and the urgings of an Aboriginal friend drove him back to the company of the natives. Finnegan turned back at the Noosa River after quarrelling with Parsons, who continued alone.3 When John Oxley sailed into Moreton Bay on the evening of 29 November 1823, Pamphlet was on the beach of Bribie Island cooking fish with the natives. He waved Oxley ashore, whereupon he learned with astonishment that he was 500 miles from home, and in the opposite direction to what he had presumed. Finnegan was away on a hunting trip but returned the next morning, and a day later led Oxley to the Brisbane River.

The man on a mission

John Oxley had been tasked with finding a site for a new penal settlement. He had been as far north as Port Curtis and was making his way back down the coast when he encountered Finnegan and subsequently made the first survey of the Brisbane River. He named it after Sir Thomas Brisbane, who was then the governor of the colony of New South Wales. Oxley explored the river as far upstream as Goodna and delivered to Governor Brisbane an enthusiastic report about the surrounding country and its prospects for a new settlement.4

Although John Oxley did not land near the CDOP site in 1823, he did record observations as he sailed past. He marked and described navigational ‘stations’ about every mile or two along the river. Station 10 was at the bend in the river at North Quay near the Grey Street Bridge, and Station 11 was near the site of the Regatta Hotel.5 Of these stations he noted:

Station 10. – From this station to the next on the same shore, the river forms a magnificent crescent of two and a-half miles of forest land. The larboard [south] shore, a thick brush with some cypress. . . .

Station 11, on Starboard Side. – Which still continues low, open forest, good grass and iron-bark trees; opposite side, rich, low brush.6

The CDOP site was at the downstream end of this magnificent stretch of forest, a part of the river that Oxley referred to as the Crescent Reach when he returned for a more detailed survey in September 1824. On that second expedition, Oxley came much closer to the CDOP site, and may have even set foot there. He travelled as far upstream as the Mount Crosby area before the depressed state of the river impeded further progress. On his way back to the bay he spent the night of the 27th of September camped in present-day Auchenflower near the site of the Wesley Hospital. The next morning he landed in present-day Milton to look for fresh water, which he found ‘in abundance and of excellent quality, being at this season a chain of ponds watering a fine valley’. The abundance of water here even in a time of drought led Oxley to note the area as suitable site for a first settlement on the river.7

There is now general agreement that Oxley came ashore near Western Creek — better known today as the Milton Drain — and found water in the vicinity of Gregory Park. Oxley’s field book is sufficiently sketchy, however, to permit the possibility that he landed closer to the CDOP site or investigated it on foot. The historian T.C. Truman, who first proposed the account of Oxley’s landing that is accepted today, even speculated that the CDOP was where Oxley found the chain of ponds.

The pre-European environment

Suppose that Oxley had ventured onto the CDOP site in 1824. What would he have seen?

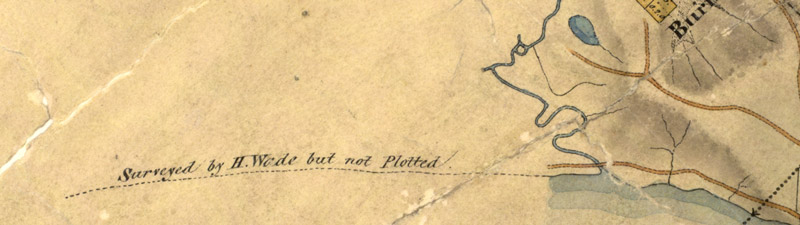

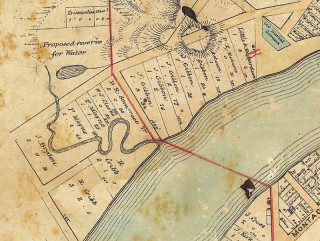

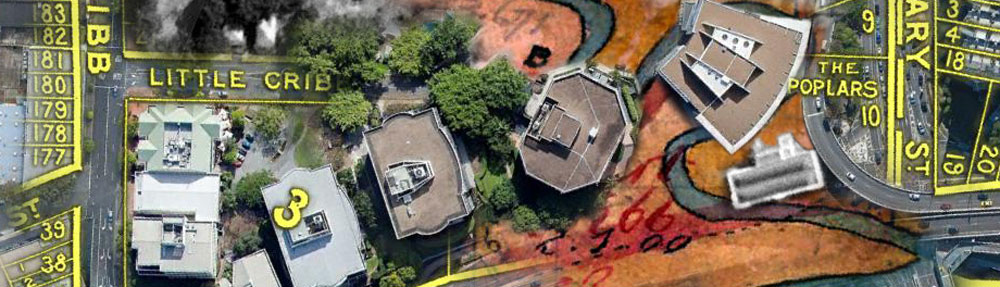

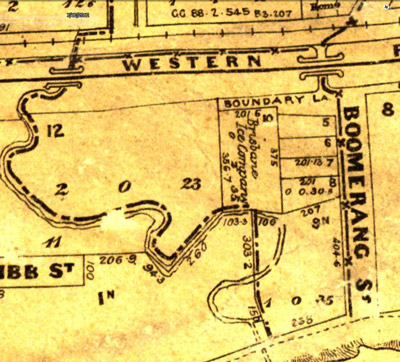

Part of the ‘Map of the Environs of Brisbane situate in the County of Stanley’, made by the surveyor Henry Wade in 1844, showing the extent of the CDOP site. (Queensland State Archives, Item ID 714302)

The first thing he would have noticed, especially since he was looking for water, was a creek. Visible on all maps of area the dating up to the early 20th century, this creek met the river where the Go-Between Bridge now meets Coronation Drive. From here it meandered across the CDOP site, taking a dog-leg turn in the north-western portion and forming a ring-like confluence where it crossed the path of the railway. It then continued upstream through a swamp where Suncorp Stadium now stands. Its headwaters were the slopes of Paddington and Red Hill.

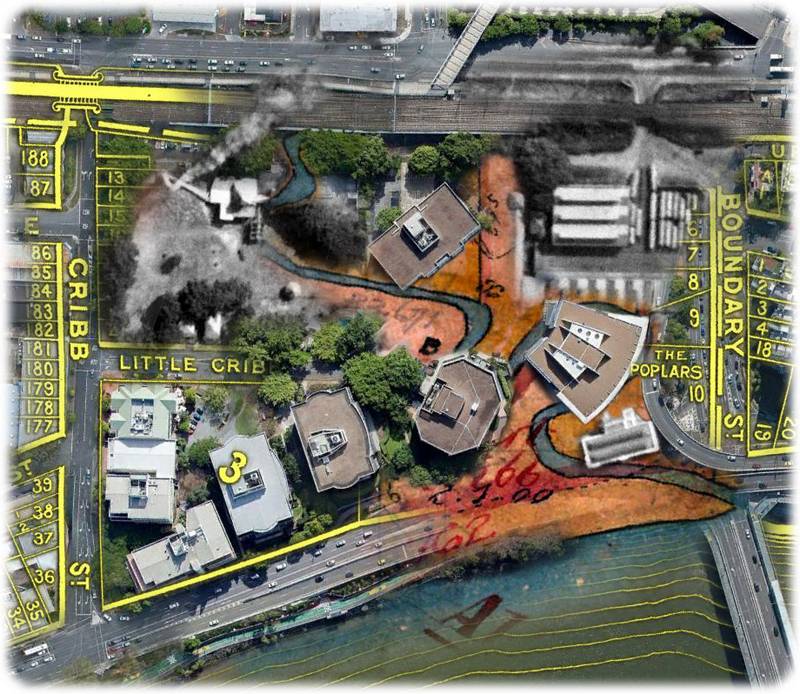

This waterway later became known as Boundary Creek. The figure to the right shows how it was depicted on the earliest surviving map of the area, drawn by the surveyor Henry Wade in 1844. The image below shows the approximate extent of the creek’s catchment area in the context of the modern landscape.

Boundary Creek as depicted on Wade’s 1844 map, overlaid on the modern landscape. The approximate extent of the Boundary Creek catchment is outlined and shaded in blue.

Boundary Creek would have been tidal throughout the CDOP site and possibly as far upstream as the stadium. The water in the tidal zone would have been fairly fresh in wet periods, but occasionally brackish in dry spells.8 The vegetation along the creek, at least at the lowest reaches, was probably a mix of mangroves and freshwater species.

Indigenous inhabitants

Something else Oxley might have noticed while searching for water was evidence of the local Indigenous people — perhaps a fishing net or a canoe by the creek, or freshly dug-up swamp fern (Blechnum indicum), the roots of which were a staple food. He certainly knew that the they were near, having had a dramatic encounter with them the night before near the site of the Wesley Hospital. In both 1823 and 1824 he observed large gatherings at the site of the Regatta Hotel.

The area was home to the Turrbal People, whose language was spoken from Logan to North Pine and as far inland as Moggil.9 Their association with the CDOP site and its immediate surrounds likely went back thousands of years. Sadly, no information about it has survived except for John Oxley’s brief accounts.

The edge of town

Despite Oxley’s enthusiasm for a site along the Milton Reach, the Moreton Bay Penal Settlement was ultimately established in 1825 on the peninsular where the central business district is today. This notoriously brutal outpost operated until 1839, during which time no free settlement was permitted except for a station established in 1838 by German Lutheran missionaries in the area now known as Nundah. I have found no records about the CDOP site during the penal colony years, but it is hard not to imagine that the area received some visitation from Europeans in this time, if only by escaped convicts or adventurous officials.

After the prisoners had left, the surveyors moved in and started to prepare Moreton Bay for free settlement. The first land sales happened in 1842, with land being offered at Fortitude Valley, South Brisbane and Kangaroo Point. But while Brisbane grew in the 1840s, the CDOP site remained un-owned and unoccupied (at least by Europeans). It was at the very edge of what Henry Wade’s 1844 map called the ‘Environs of Brisbane’. The area to the west of Boundary Creek on Wade’s map was empty, save for the comment, ‘Surveyed by H. Wade but not plotted’.

Boundary Creek was the western limit of the ‘environs of Brisbane’. (Queensland State Archives, Item ID 714302)

In 1850, the Milton Reach between Boundary Creek and Western Creek was surveyed and plotted by James Warner. His plan established the boundaries of the modern CDOP site. Roads (or at least allowances for roads) corresponding with Cribb Street, Milton Road and Boomerang Street were all marked. The River Road (which we now call Coronation Drive) was indicated by only a dotted line. Within the perimeter of these four roads the land was divided into seven irregular portions. Protruding into the site from the middle of Cribb Street was a small road that aligns with Little Cribb Street.

James Warner’s plan of 1850 defined the boundaries of the modern CDOP site. Hover over the image to see the modern landscape. (Queensland Museum of Lands, Mapping and Surveying, Plan B.1234.14.)

The city limits

The revised town boundary is marked on red on this map dating from 1858. (Brisbane City Archives, BCA POO5)

The reason for the irregular portions and the foreshortened road on Warner’s plan was the creek that meandered through the CDOP site. This creek was known by the early 1860s (if not earlier) as Boundary Creek, as it marked the natural western limit of the town of Brisbane. It was also part of the boundary separating the Parish of North Brisbane from the Parish of Enoggera.

In 1856 the creek became part of the official town boundary. The original limit of the town aligned with Eagle Terrace at North Quay and continued across the river along Boundary Street in South Brisbane. The boundary was moved in August 1856 so that it ran along the eastern edge of the CDOP site. This road had no name at the time, but it subsequently became known as Boundary Street until it was renamed Boomerang Street in 1904. The town boundary then followed the creek for a short distance to the river. The revised boundary is drawn in red on the map shown on the right, which dates from 1858.

The first landholders

Land sales at the CDOP site reported in the Moreton Bay Courier. (The lot numbers differ to those on the maps, but the lot area counts are the same.)

The seven land portions comprising the CDOP site were sold by the Crown in August 1851. The names of the buyers, as reported in the Moreton Bay Courier, were the same as those on the maps of the 1850s except for George Edmonstone, who sold his allotment to D.R. Somerset sometime prior to August 1856.10

Among these names are some eminent figures in Brisbane’s history. Three of them — George Edmonstone, Patrick Mayne and Robert Cribb — were members of Brisbane’s first City Council, and one (Edmonstone) had a stint as Mayor. Less is known about the other owners. Daniel Raintree Somerset was a public servant, appointed as Queensland’s Chief Clerk and Shipping Master in 1859 and later as the Registrar for Pensions.11 John Bryden was a carpenter and a close acquaintance of John Petrie, who was Brisbane’s first mayor and also a skilled builder. William John Clarke was either Australia’s richest man and biggest landowner or a more modest Brisbane resident who shared his name.12

Regardless of their wealth or standing, all of the first landowners appear to have shared one thing in common: none of them ever lived at the CDOP site. They bought the land as an investment, hoping either to sell it again at a higher price or to make money by farming it. Mayne used his land at the site to graze cattle which ended up in his butcher shop in Queen Street. Next to Mayne’s paddock was another farm, the name of which was synonymous with the area for several years.

Parson’s Farm

In August 1854 John Bryden advertised that he was selling his land at the CDOP site by public auction. His advertisement referred to the land as ‘a portion of the cleared ground at the Parson’s Farm’.13 This locality name made few appearances in the Moreton Bay Courier, but was used in electoral lists in the mid-1850s14 and even popped up again in 1868 in a letter to the Queenslander reflecting on the decline of dairies around inner Brisbane.

The Parson’s Farm was probably on the land originally owned by W.J. Clarke. Its namesake was George Parsons, whose only appearance in the newspaper other than in electoral lists was as part of an inquest to an apparent drowning on Mayne’s property.15

Early one morning in February 1858, Jacob Schelling, a mentally troubled German man who had been tending to Mayne’s cattle for nearly three years, was found dead in a waterhole in Mayne’s paddock. John Buckley, another of Mayne’s labourers, was the first at the scene:

I went to the hut and asked for Jacob but he was not at the hut. I went to the waterhole and found his shoes near it. I went to the creek, thinking he might he there; but he was not there. I came and told Mr. Mayne, and he came out to the paddock.

Mayne’s testimony describes the grisly discovery, and also identifies Parsons as the owner of the adjoining land:

The water-hole was in my paddock, about 150 yards from the box where [Jacob] used to sleep. I went out to the paddock and I called on Parsons whose ground adjoins it, and went with him to the water-hole. We took a long pole. Parsons brought up the deceased’s trowsers first with it. He had been washing them. He next brought up the body. . . . The body was in about 6 feet water. I think he must have been dipping the trowsers and have fallen in.

George Parsons begun his own testimony by stating, ‘I am a farmer. My land adjoins Mr. Mayne’s paddock’. Little else is known about George Parsons, but he has the honour of being the first person whose name became attached to the CDOP site.

A poor man’s earthly paradise

The advertisement for Bryden’s auction in 1854 provides what is probably the earliest surviving detailed description of the CDOP site. The land was offered in 18 allotments . . .

. . . laid out in convenient dimensions to enable the humblest working man to possess himself of a HOME, and upon terms so easy that the laying by a few shillings per week from his present remunerative earnings will enable him to become comparatively independent, and free from the payment of high rents in future.

The beautiful situation and magnificent scenery in the neighbourhood of the proposed Village of Milton, must soon conduce to its becoming a thriving and populous suburban retreat for the sons of toil when their day of labour is o’er. Numbers already daily frequent its shady and picturesque walks, leading by the gentle and wealth bearing river Brisbane, access to which is easy, by a Government road, one chain wide, contiguous to the property.

The land offered for sale is all cleared, and a very small amount of labour would convert every lot into a blooming garden; in fact, a poor man’s earthly Paradise, every way worthy of the immortal Milton.

The surrounding ridges offer every facility for procuring abundance of building and fencing materials, also abundance of good stone, brick earth, and pure fresh water, with plenty of pasture for the milch cows, so essential to domestic comfort.16

Perhaps Brisbane’s sons of toil could not afford the prices Bryden was hoping for, because the sale in August 1854 apparently did not go ahead. Bryden was advertising the same land for sale by private contract in February the following year, this time as one block rather than as subdivisions. The advertisement read:

A most desirable piece of LAND containing about 4 acres and 11 perches, be the same more or less, situated at the western extremity of Northern Brisbane, and generally known as the Parson’s Farm.

The above is admirably suited for market gardens, or Town Allotments, lies convenient to the river, and is well equipped with fresh water, and bounded on three sides by the Government Road. For further particulars, apply to the owner.

JOHN BRYDEN

Queen Street, North Brisbane, Feb. 16, 1855.17

I don’t know whether Bryden found a buyer on this occasion, and I found no mention of his land in Trove until the Milton Distillery was built there in 1870 (see below). But even though Bryden’s vision of a poor man’s paradise was never realised, others would soon start calling the CDOP site home.

A place of residence

The photograph below is probably the earliest that shows the CDOP site in any detail. The State Library’s catalogue suggests that it dates from 1874, but it could be up to ten years older than that.18 The road in the foreground is Boundary Street, and the land immediately beyond it is the CDOP site — or about two thirds of it anyway, since the site also extends beyond the right of the frame. The thick grove of trees beyond the fence hides the S-bend of Boundary Creek, while the straighter portion of the creek flows somewhere between the fence and the cottages in the right of the picture. In the centre of the picture is Ambrose Eldridge’s ‘Milton Farm’, while the white triangular roof is that of his residence, Milton House (which still stands today). Further in the distance is the distinctive profile of Robert Cribb’s house, Dunmore.

A view of Milton in the 1870s (or perhaps the 1860s). Boundary Street and the CDOP site are in the foreground, while Milton Farm and Milton House occupy the centre of the picture. The house in the foreground on the left is probably E.J. Bennett’s first residence, Sparkford Cottage, while the cottage just in front of the row of trees is probably the residence of John George Cribb. (State Library of Queensland, Negative No. 66141)

Edward James Bennett and the Poplars

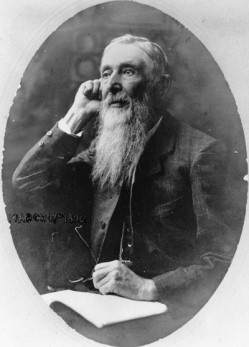

Edward James Bennett (1829-1920). (State Library of Queensland)

In this photo, various buildings are visible on the CDOP site, most of which look like little more than huts and sheds. In the foreground, however, is a more substantial cottage. This is the residence of Edward James Bennett, who came to Brisbane in about 1860 when he was appointed as Chief Draftsman of the Surveyor General’s Department, a post which he held until he retired in 1889. Bennett moved into this corner of the CDOP site in the early 1860s,19 and except for a few years that he spent in Toowong,20 he remained there until 1914, when his later residence, named the Poplars, was acquired and demolished by the Brisbane Tramway Company.

I have not determined exactly when Bennett built the Poplars, but I suspect it was in the 1880s. The photo below showing Bennett and his family at the house dates from around 1895, as does the map drawn by A.R. McKellar which shows the lot on which the Poplars was located. However, an advertisement in the Brisbane Courier reveals that he was already living in the house in 1889. He built it to replace Sparkford Cottage, which was his first residence at the site, and is probably the one visible in the photo above. Bennett died at a residence in Annerley, also named Sparkford, in 1920.

E.J. Bennett’s and his family relaxing at the Poplars, c1895. (State Library of Queensland)

John George Cribb and Fairholme

In 1917, a Toowong resident named John O’Neill Brenan presented his ‘Reminiscences of Early Toowong’ to a meeting of the Queensland Historical Society, describing his first journey out of town to the western suburbs along the River Road in 1872. As he passed the CDOP site, he saw E.J. Bennett’s residence as well as that of the CDOP site’s other long-term resident, John George Cribb:

Going back to my first journey to the neighbourhood—descending the hill from North Quay brought one to Bennett’s Bridge. This crossed a creek (long since filled up) which bounded part of E. J. Bennett’s property, hence the name given to the bridge. Mr Bennett’s house has been demolished, and the Tramways Co., I think, owns the land. Many of the trees still stand there, among them one of the very few English oaks growing about Brisbane.

Crossing the bridge, you were upon the Moggill-road, now mostly referred to as the River-road, and entered the suburb of Milton. Immediately to the right was the residence of the late John Cribb, accountant to the Bank of New South Wales. The old house stood upon the site of the present two-storeyed building in the middle of a large area, the property fronting the Moggill-road on the east side, Cribb-street on the south, and partly Little Cribb-street, the Milton-road on the west.21

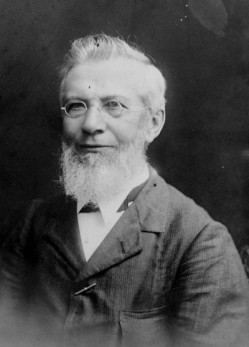

John George Cribb (State Library of Queensland)

Born in London in 1830, John George Cribb was the eldest of three sons of Robert Cribb, with whom he came to Brisbane on the Fortitude in 1849. He found work with the Bank of New South Wales within a few years of arriving, and remained with the bank until 1893, for most of that time as an accountant.22

Cribb was listed in the electoral roll as a householder at Albert Street in 1854, and as a freeholder in the western suburbs in 1856. Presumably, he had acquired some or all of his father’s land fronting the river at the CDOP site. He had taken up residence there by 1858. Cribb and his wife Lucy were heavily involved in the Milton Congregational Church, which was located near the corner of Baroona Road and Haig Road. His other great passion was horticulture, and he had a special interest in acclimatising new fruit varieties to Queensland. In a tribute written shortly after Cribb’s death in June 1905, the Colonial Botanist Mr F. M. Bailey recalled:

His garden at Milton when I first saw it in 1861 contained a goodly number of plants of an economic character, and since then he continued year after year introducing plants of the same description. . . . it is to him we are indebted for the introduction of many varieties of American grapes which of late years have been cultivated far and wide in this State. Another valuable introduction was a full collection of the best kinds of apples produced in America. These, like the grapes, have in many instances proved of great service to the fruit-growers of the State. From the same country he also obtained many varieties of the pear, quince, plum, cherry, fig, walnut, peccan-nut, blackberry, &c. In a small scrub which stood near the creek in his garden was the only place in which I have seen the mangosteen make an attempt to grow about Brisbane. The plant grew for a few years, but soon after the removal of the scrub it died. Mr. Cribb was probably the first to fruit the litchi here, and also that curious so-called fruit, the Chinese raisin (hovenia dulcis). He was the introducer of the ‘Irish peach’ apple for stock, upon which to work various varieties of that fruit; and also of that desirable stock for roses, the ‘Manetti’.

From 1864 onwards, Cribb’s name appeared regularly in the newspaper as a prizewinner at exhibitions of the Queensland Horticultural Society23 and the Acclimatisation Society.24 He was still winning prizes, not just for his produce but also for his pioneering use of new types of ploughs and other equipment, as late as the 1880s.25 Through Cribb’s efforts, it is probably safe to say that the CDOP site saw just about every type of fruit tree that could be grown — as well as many that couldn’t — in South East Queensland.

John George Cribb’s residence, Fairholme. (State Library of Queensland)

Cribb’s first residence at the CDOP site is probably the small house in the middle-right of the above photo of Milton. By 188126 he had replaced this house with a much grander residence named Fairholme. The State Library’s catalogue details for the photo on the right notes that ‘[t]he Queenslander, two-storey home was encircled by a wide verandah on three sides decorated with intricate iron lacework and topped with a widow’s walk’. Fairholme was built on the highest piece of ground on the CDOP site, more or less fronting the southern edge of Little Cribb Street. The exact location can be seen on an estate map made in 1914 when the surrounding land was subdivided and sold.

The location was well chosen, for the surrounding land was prone to flooding. A photograph of the site in the 1890 flood (which was about a metre higher than the 2011 flood) shows Fairholme in the distance as the only property untouched by the floodwater. The house stayed dry even in the flood of February 1893, which was about three metres higher than that of 1890. A report in the Queenslander observed:

Who does not know Cribb-street, Milton, with its white terraces, its trim front gardens and its general air of comfort and cleanliness? The flood water on Saturday night swept down on the locality, and before midnight the only house out of the water was Mr Cribb’s.27

Fairholme was a hub of social activity, being the venue for numerous parties, garden fetes, weddings, and funerals, including John Cribb’s own funeral in June 1905. John Cribb was survived by seven sons and two daughters. Fairholme remained in the family until at least 1924.28 Making the records from this period somewhat confusing, one of John Cribb’s sons, also named John George, built another house named Fairholme in Sherwood.29 Who says history never repeats?

Other residents

Aside from E.J. Bennett, J.G. Cribb and their families, many other people would come to call the CDOP site home, though generally not for as long as Bennett or Cribb and not in such handsome accommodation. The first Europeans to live there were probably farm labourers. Many later residents also had employment on the site, working in businesses that included sanitary stables, an incinerator and tram workshops, all of which will be discussed below.

The majority of residences at the CDOP site were on Cribb Street. Before the Fairholme estate was subdivided in 1914, most residences were on the lots between the railway and Little Cribb Street. Ater 1914, other uses occupied this area, and the majority of houses were to be found at the other end of the street. Houses remained on this part of Cribb Street until at least the 1950s.

Roads and railway

The roads that surround and define the CDOP site — Coronation Drive, Cribb Street, Little Cribb Street, and Boomerang Street — were all laid out on Warner’s survey plan of 1850 (see above), even if they were not quite the same as they are today. Over time, the site has become smaller as Coronation Drive, Boomerang Street and the railway line have become bigger.

The first road to pass the site was the precursor of Coronation Drive, known originally as the Moggill Road and later (especially from the 1880s) as the River Road, or occasionally in the 1860s as the Milton Road.30 It is shown on Wade’s 1844 map (see above), but only for a short distance beyond Boundary Creek. This is essentially where the map ends, but the depiction may have also reflected the state of the road. One account of Brisbane in the 1850s and 1860s, recollected in 1933 by a 93-year-old Taringa resident named Thomas Clancy, records that

Taringa was then connected with Brisbane by a bridle track only, the formed road extending along the North Quay to Bennett’s Creek, which was then crossed by a squared log. Prison labour was subsequently used to continue this road towards Toowong.

The road was used to transport farm produce, cattle and timber from the Moggill area to Brisbane. It was officially named River Road in 1881, and renamed Coronation Drive in 1937 to mark the Coronation of King George VI.

I can only guess at when the other roads were formed. Milton road, like the River Road, was marked with only a dotted line in Warner’s plan, and as an incomplete track in Wade’s map. It probably took shape during the 1850s as more land portions within the Parish of Enoggera were defined and sold. Boomerang Street was mentioned (though not by name, as it apparently did not have one) in the proclamation of the town boundary in 1856. Cribb Street was formally named in April 1881, before which time I can find no descriptions of it in the newspapers.

The presence of Little Cribb Street on Warner’s plan is something of a curiosity. If not for Boundary Creek, the street might have continued through to Boundary Street, but one could ask why the street was drawn into the plan at all, as elsewhere roads are generally separated by two whole land portions. Possibly, its role was to provide access to the land adjoining the southern side of Boundary Creek, as the creek might not have had a reliable crossing near the river. In any case, Little Cribb Street remained more or less as it appeared on Warner’s plan until at least the 1950s when it became part of the tram yard. It was joined to Boomerang Street when the site was developed into its present state in the early 1990s.

The railway

The railway line to Ipswich, which today forms the northern boundary of the CDOP site, was constructed in 1875, and was the first railway line out of Brisbane. It had scarcely begun operating when it struck problems at the CDOP site. As a column in the Queensland Times put it,

. . . the Brisbane and Ipswich Railway is not behaving itself in a proper manner. In plain English, it is manifesting a decided leaning towards Ipswich. This is especially noticable at the enbankment near the Milton distillery just before you get to the long cutting. That bank on the Brisbane side of the bridge seems determined to go Ipswich-way, and in its absurd effort to accomplish this is pushing the bridge before it. This is very improper, but I don’t blame the bank so much as those who gave it the inclination to take such a course. It would be interesting to discover who that “party” was, because there will be difficulties at that bridge yet. Even now the trains have to go over it “dead slow,” and when the bank gets a little farther down into the creek they won’t be able to go over it at all.31

In even plainer English, the embankment over Boundary Creek was subsiding. The writer’s ominous warning that ‘there will be difficulties at that bridge yet’ rang true 11 years later, when the line was duplicated in 1886. A new bridge was built over Cribb Street and new embankments were formed on either side of the line. Then disaster struck. As the Queensland Times reported:

An extraordinary accident took place this evening, about half-way between Brisbane and Milton railway stations, near the Milton Distillery, where a high bridge has just been erected in connection with the duplication of the line between Brisbane and Ipswich. The works on both sides of the bridge were to consist of heavy embankments. Men have been engaged for some days past, in consolidating the new embankment and filling it up with broken stones, bricks, and earth. At the spot named, the embankment had shown signs of subsidence, and, shortly after the train due at Brisbane for Oxley at 4-10 had arrived, the embankment, which had, it seems, been crumbling away, fell in with a crash, just as the 4-30 trail from Ipswich arrived on the spot. The results were extraordinary, the roadway being raised a height of 5ft. for several chains, and two water mains—12in. and 9in. each—were broken, and, immediately, the road, which is in a hollow at this place, and the neighbouring district were submerged. The rails were hanging over in a very ricketty condition, and the whole presented the appearance that might be expected after an earthquake. The theory of the cause is that the embankment, which at this place was immediately over the celebrated or notorious Milton Swamp gradually settled down, and forced back the soft swampy earth, eventually raising the road.32

This was but one of several occasions on which infrastructure at the CDOP site would fall victim to Boundary Creek.

Boundary Creek and Bennett’s Bridge

Boundary Creek is the dominant feature on the early maps of the CDOP site, and it would have been well known to early Brisbanites because it presented the first substantial crossing for vehicles and pedestrians heading out of town along the River Road. Not surprisingly, there was more written in the papers about the bridge across Boundary Creek than about the creek itself. The earliest reference that I could find was in 1861 when the Municipal Council called for the dilapidated bridge to be rebuilt. The construction job took almost a year, as temporary works were repeatedly washed away when rain turned the creek into a torrent. A few months after it was done, a landslip caused some of the road to fall into the river.

The bridge at that stage was most commonly called the Milton Bridge, and occasionally Boundary Bridge or Boundary Creek Bridge. In 1882 the name ‘Milton Bridge’ was formalised.33 However, after E.J. Bennett had settled into the locality in the 1860s, the structure was just as often known as Bennett’s Bridge.

Boundary Creek was never going to survive for very long, being on a site so close to town and surrounded by an increasing variety of land uses. By the 1870s the creek was heavily polluted, both by activities on the CDOP site as well as those upstream. Some of the pressures on the creek were described in the report of a meeting of the Milton District Board of Health in June 1878,

when the question of the nuisance arising from the creek flowing through the old cemetery was again considered. […] Complaints were also read as to the nuisance arising from drainage from the distillery; a peremptory notice was ordered to be given to the owners to discontinue the discharge of refuse liquid into the creek. A letter was received from the Queensland Ice Company, claiming the right of the water from the drainage as it now is.34

E.J. Bennett, who lived near the bridge at the end of the creek, would have seen and smelt the cumulative effect of all of the abuses committed upstream. In 1885 he wrote letters to the Toowong Shire Council complaining about the foul state of the creek and about the dams that had been created by the ice company (see below).35 Meanwhile, the old Cemetery Swamp just upstream of the CDOP site was being called ‘a hotbed of disease’, as ‘[a]ll the drainage from Petrie Terrace was being emptied into the swamp from which there was no outlet’.36

A scheme to drain the creek and swamp was finally devised in 1885. The first stage, built in 1886 at a cost of £2,518, was an 8ft-wide brickwork culvert between the railway and the river. The drain followed a much straighter path than the circuitous creek, and met the river some distance upstream from the Milton Bridge. The second stage of the drainage scheme, completed in 1887, was an open concrete drain from Milton Road to Caxton Street.37

The mouth of the creek under the Milton Bridge was now just a gully that had to be filled up. To speed up this process, the Toowong Shire Council posted an open invitation for dry rubbish to be dumped into the gully.38 The filling-up was nearly completed in June 1887,39 but for some time the channel of the creek upstream of the bridge must have remained open. The Brisbane Ice Company was seeking permission in June 1887 to ‘clean out the old creek at Milton Bridge’,40 and were later granted permission to close the pipe drain connecting the creek to the river.41 Most likely, the ice company was using the old creek as a storage dam.

Even after Boundary Creek had been pushed underground and out of sight, this waterway continued to make its presence felt, haunting infrastructure projects on the site for decades. In 1886 the embankment of the newly duplicated railway line, which had been built on top of the buried creek, collapsed in spectacular fashion (see above). In March 1889, the filling at the mouth of the old creek subsided, leaving the roadway in a dangerous condition and requiring a substantial wall to hold the riverbank in place.42 The same stretch of road subsided again forty-one years later. This time, the filling-in was not left to chance. A fleet of 31 trucks and a barge were employed to fill the cavity with stones from three of the council’s quarries. The newspaper report, which was accompanied by a large pictorial spread, made special mention of the old buried creek, citing it as the probable cause of the landslide.

A site of industry

The CDOP site in the 1850s and 1860s was primarily farmland scattered with a few houses. Agricultural uses continued into at least the 1880s, with market gardens operating alongside J.G. Cribb’s more experimental activities. In the 1870s, new kinds of industry began to arrive at the CDOP site.

The Milton Distillery (1871-1889)

Early in 1871, a distillery was built on the land fronting the northern end of Cribb Street. It boasted a novel technical design and was claimed by some (though not all) to be Queensland’s first rectifying distillery.43 The physical particulars of the distillery were described in the Brisbane Courier:

The building has an extreme length of sixty foot by a width of twenty, and is divided into two stories. Brick and stone form the materials of which it is composed, and the flooring of the second story is of beech. The ground floor is divided into a bonded store, a room to be used for the storing of the materials employed on the works, and still-house, each twenty foot by twenty. On the upper floor is the fermenting room, in which will be fitted twelve vats each estimated to hold 1100 gallons. The still is capable of containing 800 gallons, and is fitted with a syphon refrigerator in a galvanised iron tank. The copper rectifier is capable of holding 1500 gallons, and seems to be an excellent piece of workmanship. The steam boiler, which is of sufficient dimensions for the use of the establishment, is placed in a commodious shed outside the main building. There is also another large and strongly-built shed, which will be used for bottling and other purposes.

. . . The building stands upon an allotment of about an acre in extent, and presents a plain substantial appearance. Mr. Samwell, the proprietor, is a new arrival, being not more than a year in the colony, and certainly deserves a great credit for the spirit and enterprise which he has evinced in embarking his capital in initiating an industry of this kind. Every description of spirituous liquor will be manufactured on the premises, and with a protective duty of one-third the amount paid upon imported spirits, there is every likelihood of a large trade being done.44

The Milton Distillery in flood in 1890. In the background, the residences of E.J. Bennett and J.G. Cribb are also visible. (State Library of Queensland)

Probably the only surviving photograph of the distillery is the one shown above, which was taken during the flood in 1890. The photographer would have been standing on the railway line, possibly on the bridge over Cribb Street, looking east-south-east towards the opposite corner of the site. On the front of the building are the words ‘Milton Distillery Comp. Estab. 1870’.45

The front of the Milton Distillery building, still standing in 1949. (Brisbane City Archives, BCC-B54-280)

Although the distillery closed in 1889, the building remained in place for many years. In his ‘Reminiscences of Early Toowong’, written in 1917 but describing a journey along the River Road in 1872, John Brenan recalled:

There were a couple of cottages between Little Cribb-street and the Milton-road, and immediately on the corner of the latter was the Milton Distillery, which was, I think owned by the Forsyth family and the inspector was Mr. A. E. Douglas. The word “Distillery” has been deleted but “Milton” remains, and the place is now occupied as a dwelling-house.

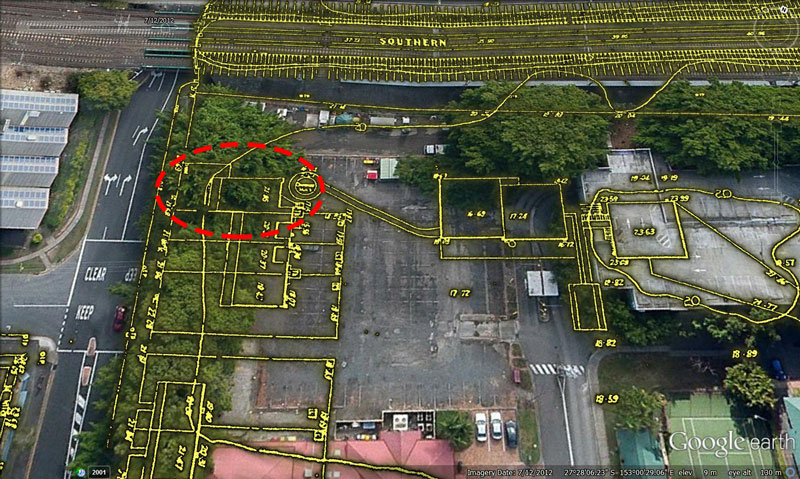

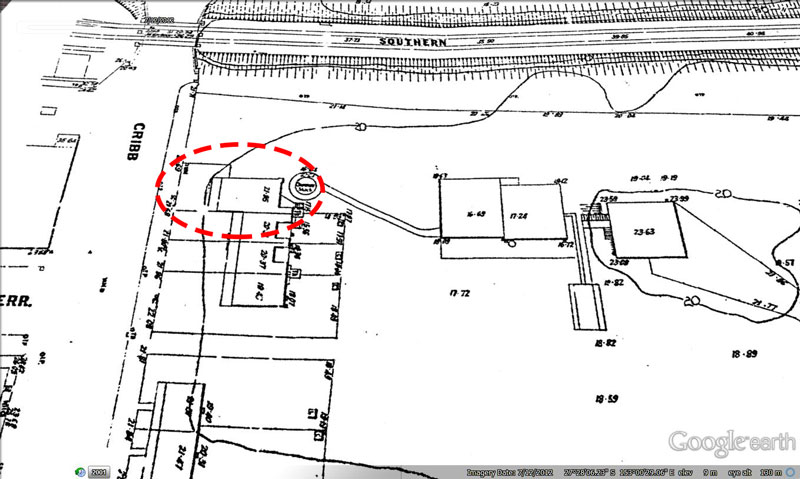

The building was there until at least 1949, when the Brisbane City Council purchased the land to expand the tram workshops (see below). In July of that year, someone in the council took the photograph on the right, which shows the front of the building that was photographed in the 1890 flood and described by Brenan. Knowing that the building was standing as late as 1950 means that we can identify it on the City Council’s ‘detail plan’ of the site, which dates from 1927. The relevant part of the plan is shown below, with the distillery bulding circled. While nothing on this plan identifies the building, the surveyor’s field book provides the necessary information to do so.

The location of the Milton Distillery building indicated on the Water Supply and Sewage Board’s Detail Plan 122, dated 1927. Hover over or tap the image to see the modern landscape.(Brisbane City Archives)

The distillery produced rum, distilled wine and other spirits, but rum was the staple product. After 18 months of operation, William Samwell’s rum won first prize in the Intercolonial Exhibition in Sydney.46 In the 12 months to 31 March 1872, the distillery produced 18,555 gallons of rum, equal to about one sixth of Queensland’s total production.47 The following year, the distillery produced 34,498 gallons, a touch over one fifth of Queensland’s total.48

By that time, Samwell was no longer running the distillery. After losing a contractual dispute with his coppersmiths, he was forced to give up the distillery in December 1871.49 The new owner was Robert Forsyth, who ran the business until 1876 when he had a contractual dispute of his own and also got into trouble with the Inspector of Distilleries for operating with an expired licence.

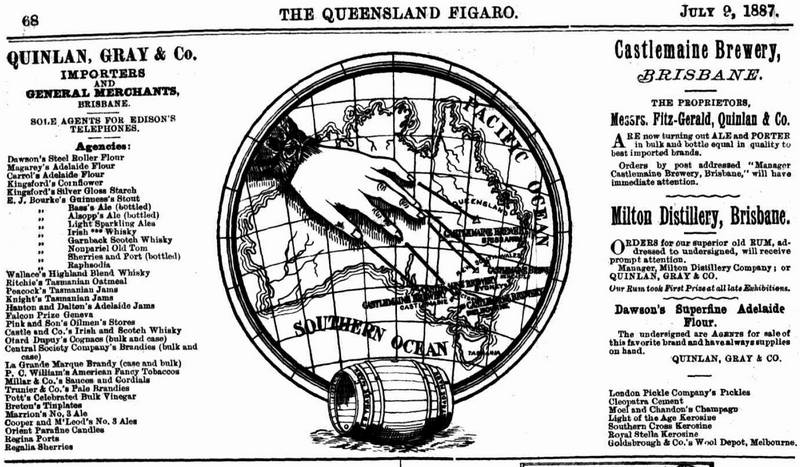

The next and last owners of the distillery were the brothers Nicholas and Edward Fitzgerald, who were well-known brewers from Castlemaine, Victoria.50 With their partners, trading as Quinlan, Fitzgerald and Co., the Fitzgerald Brothers established the Castlemaine Brewery at the site of the current brewery in September 1878.51

Quinlan and Co. ran the distillery alongside the brewery until the distillery closed in 1889.52 In the 1895 post office directory, the distillery site is listed as ‘Wilson, Quinlan, Gray & Co steam mills’, suggesting that the company found other uses for the site after the distillery closed. The vacant distillery was still listed in the 1907 directory, but by 1911 the building had become a residence.

An advertisement published in 1887 for Quinlan, Gray & Co, who owned the Milton Distillery and established the Castlemaine Brewery on Milton Road. (Trove)

The ice works (1876-1883)

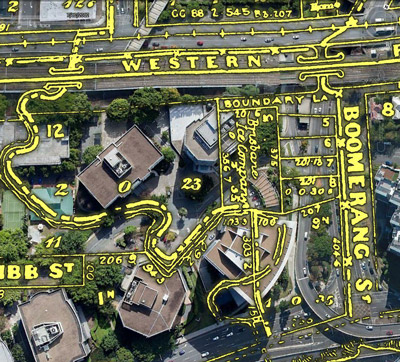

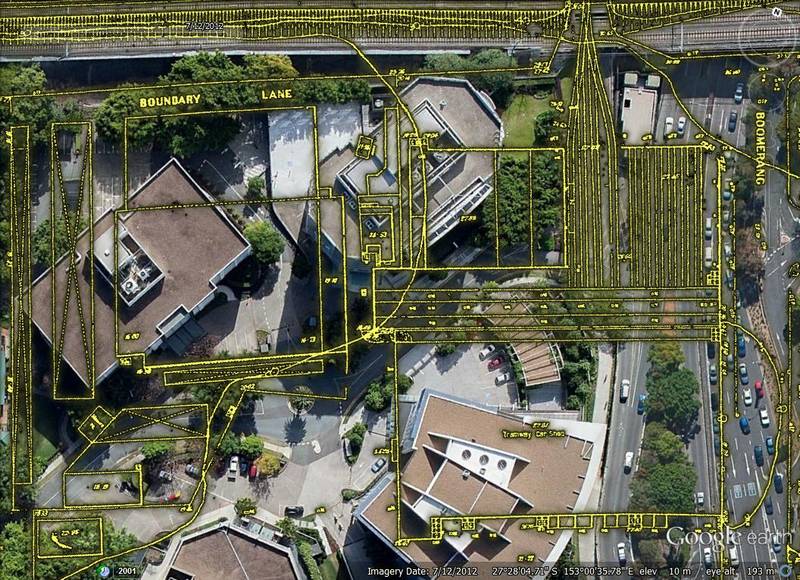

The Brisbane Ice Company’s premises are marked on this map published in 1914 but mostly showing details from the 1880s. (Queensland State Archives, Item ID 618816)

Before the invention of electric fridges, ice was made in steam-powered factories. One such factory was established on the CDOP site in 1876, when the Queensland Ice Company set up their plant in the corner between the railway line and Boundary Street. The exact location is marked on the map to the right. As the image shows, the ice company’s premises did not front Boundary Street but were instead accessed by the now non-existent Boundary Lane. The site also backed onto Boundary Creek just upstream of E.J. Bennett’s residence.

The machinery installed by the ice company in 1876 had been imported from London but built to a patent originating in Geelong. According to a description in the Brisbane Courier,

The principle of the process used is the production of cold by the evaporation of ether in vacuum, and the conveyance of the cold, by the agency of brine, to the water operated upon. The evaporated ether is pumped through a large number of pipes in the refrigerator, which is a cylindrical vessel full of tubes. […] The necessary pumping power is supplied from a 80 horse-power Cornish boiler, and a horizontal engine equal to 20 horse-power. The Enoggera water is purified with alum for making the ice, and is also used for the boiler; but for all other purposes water is pumped up from a salt water creek close by, and condensed.

In 1883 the Queensland Ice Company wound up53 and the premises and equipment were purchased by the Brisbane Ice Company, which was already operating a plant at a location near the present Parliament House.54 The company’s director was Owen Gardner, who also owned the soft drink company Owen Gardner and Sons, which later merged with a rival to become Kirks.

The Brisbane Ice Company consolidated their operations at Milton, and after upgrading their machinery could produce six tonnes of ice per day. The company also modified the creek to better serve their operations. As a report in the Brisbane Courier in October 1884 explained,

The water required for the works is obtained from a well on the premises, 6ft. by 6ft., and about 25ft. deep, which is supplied from a creek hard by. The supply of water in the creek is maintained by three dams, which always kept it at a certain level and regulate the influence of the tide, as the creek runs into the river.

The ice company received repeated requests from their neighbour, E.J. Bennett, as well as the Toowong Shire Council to remove obstructions from the creek. They continued to dam the channel of the creek even after its connection to the river was blocked in 1887.55 But by this time the ice company was on its last legs. Struggling after a wet and relatively cool summer, and in the face of stiffening competition from the Queensland Ice and Freezing Company (based at North Quay), the Brisbane Ice Company voluntarily wound up in late 1887 and its operations on the CDOP site ceased.56

Stables, garages and other businesses

Dell Price’s garage was located near the corner of Coronation Drive and Cribb Street. (Trove)

Other than the distillery and the ice works, the most notable industrial activities on the CDOP site were the sanitary depot and the tram yards, each of which are discussed separately below. Operating alongside these was a range of other businesses and individual traders, many of them allied with the larger enterprises.

Along the River Road from about 1915 onwards there were various stables, storage sites and mechanical garages. These included a Kerosene bond, Thomas Healsop & Co.’s stables and bulk storage, Morrows Ltd Stables, Dell Price’s motor service station, Safe Brakes Pty Ltd, Federal Furniture, Highway Homes and Fowlers Drive Yourself Cars. In the early 1980s there was a Datsun car yard near the corner of Cribb Street and Coronation Drive.57

The Morrows Ltd Stables were associated with the Morrows Ltd biscuit factory which was located on the city side of Boomerang Street. Morrows merged with Arnott’s in 1949, and the factory operated at Boomerang Street until the 1980s.

A hub of sanitation

The sanitary stables (1898-1940s)

In the late 1880s, a debate was being had in Brisbane about how best to manage the disposal of the city’s nightsoil, otherwise known as human faeces. At that time, most of the city’s nightsoil was being buried in shallow trenches on St. Helena Island, 21km east of Brisbane in Moreton Bay. St Helena was at the time also being used as a prison. The island’s sandy soil barely contained the refuse, and the resulting smell was so bad that the governor of St. Helena took pity on the prisoners.58

In that same year, a man named E. Parr Smith devised a plan to dump the nightsoil at sea. He took his plan directly to the mayor (bypassing the tendering process that was underway), and in quick order also won the endorsement of the premier, who recommended that the council accept his proposal. Amid considerable controversy, Smith and his partners were awarded a contract, and in January 1890 commenced operations as the Brisbane Sanitary Company.59

Under the contract, the sanitary company would collect nightsoil from the suburbs and load it onto a steamer which would take it down the river and outside Moreton Bay before dumping it into the ocean. While most of the operations would take place at a wharf and at sea, the company had to maintain a fleet of horses, carts and other equipment, which is where the CDOP site came in. As the Brisbane Courier explained,

The company have built a stable and a depot for the carts at Milton, and the entire plant of Dobbyn and Co. [the previous sanitary contractors] has been acquired. This plant comprises thirty-three waggons, eight night carts, four drays for carting dry earth, two drays for removing dead animals, and fifty-six horses.60

The company’s depot was listed in the post office directory as being near the top of Boundary Street. Most likely, it occupied the site of the Brisbane Ice Works, which had closed down a few years earlier. The Brisbane Sanitary Company ran the depot until 1900, when the city’s sanitary contract was awarded to Henry Carr from Brighton, Victoria. Carr’s company, which in about 1924 went to his sons Justin and William, would hold the city’s sanitary contract for another 50 years.

The sanitary depot maintained an uneasy coexistence with the surrounding residents. In 1913, householders in Milton submitted a petition begging the Health Department to intervene and prevent the sanitary company from depositing offensive rubbish on the site. At times, the smells from outside the site might have been as bad as any coming from the sanitary depot. Milton in the late 19th century was densely populated, but many of the neighbours of the CDOP site could not afford nightsoil collection, so instead they dumped their refuse in their low-lying, flood-prone backyards.

The nightsoil dump (1928-1940s)

Brisbane continued to dump its nightsoil into Moreton Bay until 1928, when a new scheme was devised to dump it at Milton instead. Although the suburbs were not yet sewered (and would not be for many years), a main sewage pipe had been built from Toowong to the treatment works at the mouth of the river, passing the CDOP site and the Carr brothers’ sanitary depot along the way. All that needed to be done was to connect the sanitary depot to the sewer.

So began the Milton nightsoil dump. I’ve found no plan or picture of the building, but it was most likely located between the tram workshops and Carr’s incinerator (both discussed below). The Brisbane Courier described the dump’s operation:

The dump is a concrete structure, and about 50,000 pans will be taken to it each week. The contents of them are flushed through screens by heavy pressure of water at an average of six gallons a pan to the sewer at North Quay. The pans are carried over a series of rollers to a trough for cleansing, and are then taken on a conveyor for stacking. Machinery has been installed for reducing the sawdust chips to a small size to facilitate the work of the dump. The introduction of this system will obviate sanitary carts traversing the main streets, and the use of sanitary steamers and a wharf at North Quay for the berthage of them.61

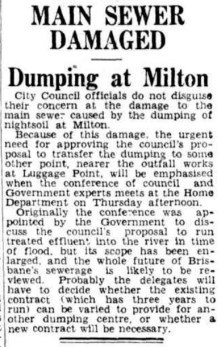

Concerns about the state of the main sewer were raised 12 months before it collapsed in April 1940. (Trove)

Enthusiasm for the scheme did not last long. Two months after the scheme commenced, there was a major blockage in the main sewer at Milton. A gang of workers toiled for two weeks to unblock it, one of them dying after succumbing to the trapped fumes and falling down a shaft. The blockage was caused by sawdust, which had been mixed into the nightsoil with insufficient water at Milton. When the sewer was unblocked, the dump recommenced its operations, much to the disgust of local residents who complained that the smells from the depot made their houses uninhabitable.

In 1932 a deeper flaw in the scheme became apparent. The pipes of the sewer main had been slowly deteriorating, and the prime culprit was the gas generated by the stale, sawdust-laden sewage from Milton. A Council engineer’s report into the pipe damage confirmed these suspicions, but incredibly, the scheme was allowed to continue, despite mounting opposition from both within and outside the council.

The final straw came in April 1940 when the sewer main collapsed at Pinkenba. Poor design of the sewer was partly to blame, but so too were the corrosive gases generated by the 500,000 gallons of sewage that came from Milton each day. Dumping at Milton was halted immediately, and Lord Mayor Chamberlain hoped that it would not recommence. However, the disposal contract still had three years to run, and an internal council memo from staff at the tram workshops shows that the dump was still operating — and still stinking — in 1943.

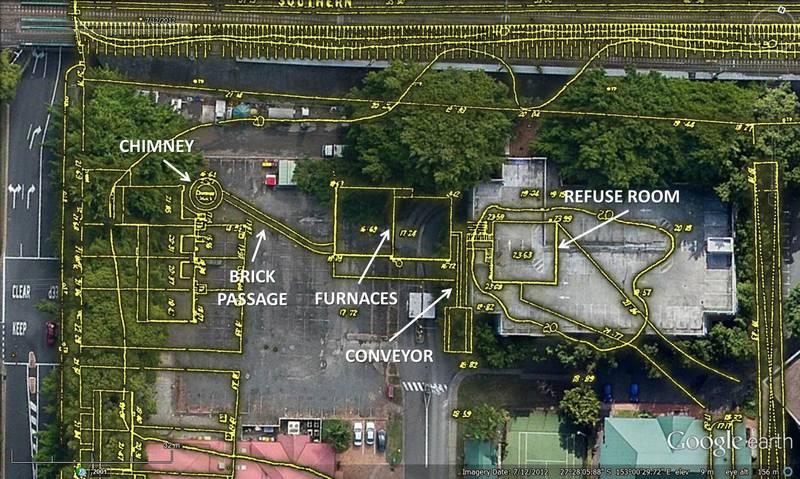

The incinerator (1918-1950)

In June 1918, a notice appeared in the Brisbane Courier alerting readers to ‘the proposed erection of a garbage destructor at Milton’. Local residents quickly mobilised against the proposal, gathering 1,351 signatures on a petition presented to the Toowong Council. In the following months, correspondence flowed between Henry Carr and the council, the latter expressing strong opposition and the former insisting that there was nothing to worry about.

Carr won the battle, and the incinerator was in operation by February 1922, which is when complaints about it started appearing in the paper. The incinerator received some more positive press in November 1927, when the Sunday Mail ran a pictorial spread describing in considerable detail the incinerator’s operations and its ‘big task’ of ‘keeping the city clean’.

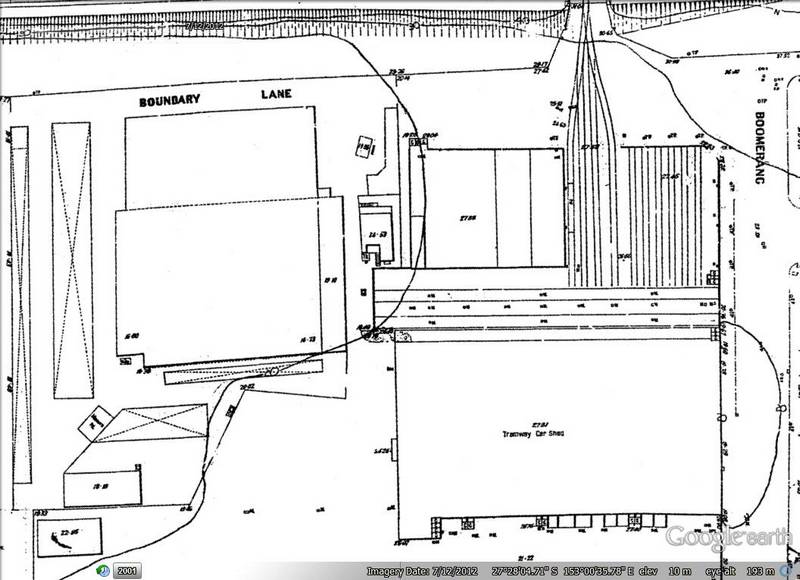

The incinerator was built on land that was originally attached to the Milton Distillery. The various components of the incinerator, as drawn on the Water and Sewage Board’s plan of the site from 1927, are shown below, with labels derived from the surveyor’s fieldbook.

The Milton Incinerator was depicted on the City Council’s Detail Plan from 1927, shown here over the modern CDOP site.

The incinerator’s chimney was for a time the highest in Brisbane, standing at 130ft in 1937 and 160ft in the late 1940s.62 Smoke can be seen billowing out of it in the City Council’s aerial photograph from 1946:

The Milton Incinerator is visible in the upper-left corner of the CDOP site in this 1946 aerial photograph. The Carr brothers’ sanitary stables were in the adjacent lot. On the right-hand side of the site, and also fronting Coronation Drive, are the tram workshops and administration building. Hover over or tap the image to see the modern landscape.

Garbage from most of Brisbane’s metropolitan area was incinerated at Milton. In 1927, the incinerator operated around the clock except for one Sunday each month. By 1937 it was operating every day of the year and employed about 25 people, many of whom lived in the adjacent houses where they could keep watch for fires.

All kinds of garbage were incinerated here. As well as general household refuse, the incinerator disposed of confidential government documents, confiscated narcotics, and rats from the city’s wharves and laboratories. Among the few things that were excluded were unbroken bottles (which were re-used) and any dry material that could be used to fill up the city’s swamps (this is how Gregory Park and many other parks in Brisbane’s parks were formed). Occasionally, things found their way in that should have been kept out, such as explosives and volatile chemicals. In 1947, an unexploded aerial bomb was discovered just before being shovelled into the furnace. In 1942, a worker fell onto the conveyor and narrowly escaped being drawn into the flames.

On one occasion, a valuable item was retrieved from the incinerator after it had been through the furnace. In 1944, 25 milligrams of radium in a gold tube, worth more than £200, went missing from a doctor’s surgery in the city. A lecturer in bio-physics at the University of Queensland named D.F. Robertson searched the surgery with a Geiger counter and concluded that the radium must have ended up in the trash, which in turn must have gone to Milton.

Mr. Robertson visited the City Council’s incinerator at Milton and ransacked the mountain of rubbish there. He found dead dogs and refuse of every description — but no tube. Then he decided to make a daily check on ashes from the furnace. As he worked with his detector, nearby residents saw the strange spectacle of a man wearing ear phones, and going over the dump, waving what seemed to be a long wand with a tin on the end.

Mr. Robertson did not know in what shape the tube would emerge from the furnace, and he came across many objects that looked more like tubes than the real thing did, when, on his third day, he discovered it in the ashes. It then was a misshapen blob of black metal — but the radium, in its protective inner sheath, was intact.63

The ashes from the incinerator were used to build up the ground on the site, including the depression left by the old Boundary Creek. Flower gardens flourished in the ash-enriched soil. The ashes were also used to fill in the swampy ground at Lang Park.

The City Council decommissioned the incinerator along with the rest of the sanitary depot in 1948 and bought the land in June 1950 to expand the tram workshops. The iconic chimney came down later the same year.

A hub of transportation

The tram workshops

In May 1914, an area of 49 perches on Boomerang Street was resumed with the intention of establishing a new power-house for the city’s tram network, then operated by the privately owned Brisbane Tramway Company. Two months later, E.J. Bennett’s ‘Poplars’ residence, which had been standing at the south-east corner of the CDOP site for about 50 years, was torn down. No power-house was ever built there (it was eventually built at New Farm), but the Tramway Company retained the land and used it for stables.

In February 1924, the Tramway Trust (the Council-owned entity that took over the trams in 1923) resumed a further acre of land at the CDOP site to build new workshops, as the existing facilities at Countess Street had become inadequate. The new workshops were completed in 1928 and were situated near the railway at the north-eastern corner of the CDOP site. In the following year, the City Council (which took over from the Tramway Trust in 1925) built a new administration office for tramway staff on the corner of Boomerang Street and River Road.64

The tram workshops were built in 1927, the same year as the Council’s detail plan for the site was drawn. They occupied the north-east corner of the site, but would later expand. The outlined buildings on the left side of the figure are the Carr brothers’ sanitary stables. Hover over or tap the image to see the modern landscape.

The tram workshops, 1968. (Brisbane Tramway Museum)

During World War II, the tram workshops produced sprocket wheels for the caterpillar treads of army tanks, as well as ‘dummy’ wooden guns that were designed to fool the Japanese into thinking that Brisbane was well defended.65 After the war, the workshops were duplicated to increase the production of trams and replace the aging fleet. By 1949, the workshops employed 450 employees and were turning out a new tram every three weeks. All parts were made at the site except for motors, wheel centres and brakes. The site even included a printing press for tickets, signs and advertising.

Still hungry for space, the council resumed the property of the sanitary depot and the incinerator in 1950. The plan was to build a bus and tram depot on this land, but later photos of the site suggest that buses were simply parked on the grass. The council had hoped to acquire the entire CDOP site at this time, but a building application for the expansion of Dell Price’s garage stood in the way.66 The south-east corner of the site was never resumed, and today is still owned and operated separately from the rest of the site.

After Brisbane’s tram services ended in April 1969, many trams were destroyed on the CDOP site. Buses were likely kept at the site until the administration centre at the CDOP site was closed in 1978-9. All of the council’s buildings and facilities were demolished, leaving most of the site unoccupied for the first time since 1850.

Trams being destroyed in 1969. (Brisbane Tramway Museum)

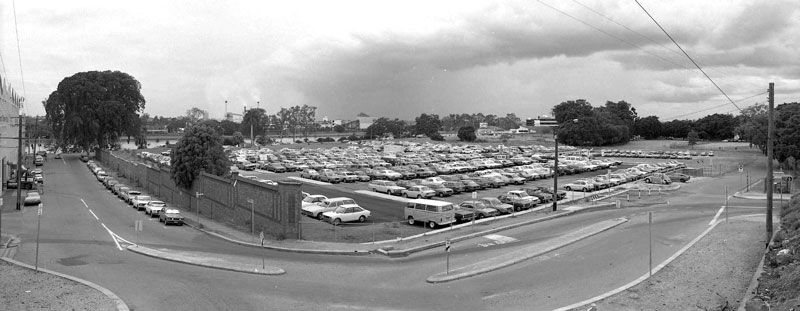

The Park-and-Ride

The CDOP site had been a crucial hub of Brisbane’s tram and bus network for more than 50 years when the transport office and bus depot closed. In the 1980s the site made one more contribution to the city’s transport system by hosting Brisbane’s first ‘park and’ ride’ car park. This scheme enabled commuters to park their cars just outside the city and finish their journey by bus or train. The car park covered only the eastern side of the site, while the council’s land on the western side remained undeveloped. In the original version of the image shown below, you can see in the south-west corner of the site a Datsun car centre and an office building owned by VACC insurance.

In the mid-1980s, the council settled on a new direction for the site, and in 1986 they called for tenders to design an office park. The development of the present site commenced in the early 1990s.

Celebrating an unglamorous history

For a site covering just a few hectares, the Coronation Drive Office Park has a surprisingly rich history. While many uses of the site over the years have been (to put it mildly) less than glamorous, they nonetheless have been of great significance in the development of Brisbane, and arguably Queensland as well. John George Cribb’s efforts to acclimatise new fruit varieties and pioneer new farming technologies surely earned the site a place in the state’s horticultural history.

The site’s non-agricultural industries were also of local and regional importance. The Milton Distillery addressed a shortage of local rum supplies in the 1870s and accounted for a sizable share of the state’s production. The nightsoil dump and the incinerator played a vital role in Brisbane’s sanitation in the first half of the twentieth century, disposing of much of the city’s garbage and sewage. From the late 1920s the site was a crucial hub of Brisbane’s public transport system, being the place where many of the city’s trams and buses were built and maintained. As the city’s first park-and-ride car park during the 1980s, the site made one final contribution to the evolution of public transport in Brisbane.

As the uses of the site have changed over the years, so too has its landscape. There is little evidence now of the meandering, tidal reaches of Boundary Creek, and you have to look closely to notice the hill that kept Fairholme dry in the 1893 flood. I never learned when the Moreton Bay figs were planted, but judging from the 1946 aerial photo, these trees have been one of the few constants on the site over the last three quarters of a century.

The filling in of Boundary Creek was perhaps the defining act in the site’s history. It fused two separate pieces of land into one, opening up new opportunities for how the site could be used. Despite erasing part of the site’s history, this act served to preserve some of it as well. Among the rubbish used to fill in the creek were the ashes from the Milton Incinerator, and undoubtedly other junk from around the site. Quite literally then, a chapter of the site’s history lies embedded in its built-up grounds.

As part of the site gets redeveloped over the coming months, perhaps some of this buried history will be unearthed. An old rum bottle, a molten jam tin, a part of a tram — who knows? Even if none of the site’s history is resumed physically, there is still an opportunity to resurrect it symbolically. Perhaps a water feature in memory of Boundary Creek, a bar in honour of the distillery, a fruit tree or plough to remember John George Cribb, or (my personal favourite) a toilet block in memory of the sanitary depot.

A recent initiative of the City Council has already made some aspects of the CDOP site’s history more visible. During the course of this investigation, the council erected a handful of educative signs on the site as part of the Meander through Milton Heritage Trail. There’s also a trail called Reminisce in Rosalie, as well as a very informative installation at the mouth of Western Creek. Despite getting an eerie feeling that the council’s historian and I are somehow stalking one another, I am heartened to see that the area’s history is getting so much attention. And I am glad to have given it a little bit more.

Thank you to AMP Capital for supporting this research.

Notes:

- Except for half a hectare at the corner of Coronation Drive and Cribb Street, the site is owned by AMP and Sunsuper. ↩

- Pamphlett’s account of the castaways’ misadventure was documented by John Uniacke, a member of Oxley’s crew. A Reproduction of Pamphlett’s narrative is available at SEQ History. The Wikipedia articles for Thomas Pamphlett, Richard Parsons and John Finnegan provide additional background. ↩

- Parsons continued for several hundred kilometres before the intensifying heat tipped him off to the fact that Sydney might be in the opposite direction. He returned to Bribie Island, from where he was collected by John Oxley in September 1824. ↩

- Oxley’s own account of his 1823 expedition up the Brisbane River is available at SEQ History. ↩

- I have taken the station locations from T.C. Truman’s article, ‘Rewriting the history of Brisbane’s birth‘, printed in the Courier Mail on 3 May 1950. ↩

- From the reproduction of Oxley’s journal at SEQ History. ↩

- John Oxley’s field book from the 1824 expedition is reproduced in J.G. Steele’s The Explorers of the Moreton Bay District 1770-1830, published in 1972 by University of Queensland Press, St Lucia. All further references to Oxley’s 1824 visit are based on this source. ↩

- See Section 2.2 of the full report for more information about this topic. ↩

- Most of what is known about the Indigenous people of Brisbane derives from the account of Thomas Petrie. Thomas came to the Moreton Bay settlement as a child in 1837 with his father Andrew Petrie, a builder who was assigned as the colony’s Superintendent of Works. With few other white children to play with, he mingled freely with the locals, learning their language and customs. His experiences were recounted by his daughter Constance Campbell Petrie in her book Tom Petrie’s Reminiscences of Early Queensland, published in 1904. A reproduction of the text is available at SEQ History. ↩

- Somerset is mentioned as the owner of the lot fronting Boundary Street in the proclamation of the revised town boundary in 1856. Although Warner’s plan dates from 1850, many of the names and other markings on it are later annotations. ↩

- Somerset’s appointment as shipping master was reported in the Moreton Bay Courier on 27 December 1869. His position as registrar for pensions is mentioned in passing in this article about St John’s Wood. ↩

- See the full report for more information about these landowners. ↩

- The Moreton Bay Courier, 26 August 1854. ↩

- For example, this list of July 1854 ↩

- In The Mayne Inheritance, Rosamond Siemon speculates that Schelling may have been murdered by Mayne, citing the coroner’s opinion that the body did not present the typical signs of death by drowning. ↩

- The Moreton Bay Courier, 26 August 1854. ↩

- The Moreton Bay Courier, 17 Februay 1855. ↩

- . A newspaper feature about the site published in 1930, with input from a member of Bennett’s family, suggests that the same photo dates from 1865. ↩

- The Courier reported the birth of one of his children at Milton in November 1862. ↩

- The Queenslander, 24 September 1931. ↩

- Brennan’s reminiscences were published in The Sun over three weeks beginning on Sunday, 1 July 1917. Extracts are also reproduced in: John Pearn (1997). Auchenflower: The suburb and the name. Amphion Press, Brisbane. ↩

- Sourced from J.G. Cribb’s obituary in The Queenslander, 17 June 1905. ↩

- The Courier, 18 January 1864. ↩

- The Queenslander, 27 July 1872. ↩

- For example, The Queenslander, 30 August 1884. ↩

- The Brisbane Courier‘s notice about the marriage of Cribb’s eldest daughter, Lucy, in March 1881, mentions Fairholme. ↩

- The Queenslander, 11 February 1893. ↩

- The house is mentioned in a the engagement notice for J.G. Cribb’s son (or possibly grandson) in 1924. ↩

- See J.G. Cribb Jnr’s obituary, printed in the Queenslander May 1926. ↩

- For example, see this picture in the State Library’s collection and this report in the Brisbane Courier, 1865. ↩

- Queensland Times, 28 September 1875. ↩

- Queensland Times, 9 September 1886. ↩

- The Brisbane Courier, 6 July 1882. ↩

- The Brisbane Courier, 14 June 1878. ↩

- The Brisbane Courier, 6 August 1885. ↩

- The Brisbane Courier, 18 December 1885. ↩

- The Brisbane Courier, 1 July 1887. ↩

- The Brisbane Courier, 11 December 1886. ↩

- The Brisbane Courier, 24 June 1887. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- The Brisbane Courier, 8 July 1887. ↩

- The Brisbane Courier, 20 March 1889. ↩

- This meant that the distillery employed a ‘fractionating’ or ‘rectifying’ column through which the evaporated alcoholic solution would rise, undergoing successive cycles of vaporisation and condensation until the desired strength was obtained. Based on a design perfected by the Irishman Aeneas Coffey in 1830, rectifying distilleries enabled continuous and efficient production of spirits. The simpler, traditional method of distillation involved channelling the vapour directly into a condenser, a process that often had to be repeated many times to achieve the desired strength. (For more, see Distillation on Wikipedia.) ↩

- The Brisbane Courier, 4 February 1871. ↩

- Don’t bother trying to make out the words on this version — you can only read them on the original. ↩

- The Wallaroo Times and Mining Journal, 8 November 1871. ↩

- The Brisbane Courier, 2 July 1872. ↩

- The Queenslander, 5 July 1873. ↩

- The Brisbane Courier, 6 December 1871. ↩

- The Maitland Mercury & Hunter River General Advertiser, 21 July 1877. ↩

- This link between the brewery and the distillery seems to have caused some confusion. The history page of the XXXX website, for example, states twice that the brewery and the distillery were on the same site. ↩

- The Brisbane Courier, 6 August 1889. ↩

- Queensland Government Gazette, Vol. 33. ↩

- The Brisbane Courier, 8 May 1833. The premises were on Short Street, which no longer exists. ↩

- See the Brisbane Courier, 3 September 1885, 29 October 1885, and 18 August 1887. ↩

- The Brisbane Courier, 7 May 1887 and 1 November 1887. ↩

- These businesses are listed in the Queensland post office directories from the years mentioned. ↩

- The Brisbane Courier, 10 April 1889. ↩

- The Brisbane Courier, 28 December 1889. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- These heights were cited in the courier mail in November 1937 and September 1950. I am assuming that the chimney was rebuilt or extended in the intervening time. Alternatively, the chimney might have been unchanged while one of the newspaper reports described the height incorrectly. ↩

- The Sunday Mail, 23 July 1944. ↩

- The Brisbane Courier, 3 August 1929. ↩

- The guns are described and pictured in the City Council’s booklet for the Meander through Milton Heritage Trail. ↩

- Tramways Correspondence, Brisbane City Archives, BCA0967. ↩

I work at this office park and was delighted when my random late-night search on the history of the milton office park in Google actually turned up with something! Excellent work on documenting the history, it is quite interesting and very well-presented.

This was a very exciting article for me to have found as I am a direct descendant of the George Parsons (he was my grt grt grt grandfather). Have been trying to find information about him for quite some time. Would it be possible for me to have a copy of your excellent article showing exactly where George and his family lived. George arrived on board the “Florentia” in 1853 with his wife, Maria, family of

four children. They were Emily, Diana Grace, Mary Jane and my grt grt grandfather George Alfred. Hope to hear from you

regards

Marion Hall nee Parsons.

Wonderful to hear from you, Marion! I was especially intrigued about George Parsons, because I could find so little information about him. I’m happy to provide you with anything I can, although I’m not quite sure what article you are referring to.

I have 3 pieces of Furniture that came from the wood out of Brisbanes old Arnotts Factory. I was trying to find out what kind of wood it is.

The wood is 100 years old and was bought from the factory, when it was refurbished. The Sweet Lillian Furniture Co bought the wood and turned it into a Wall Unit, a Table, and a small Table. I was wondering if someone had any memories of this wood as I would like to identify the type

I am researching the sugar planters development along the Albert River, an area known as ‘Noya’ . Articles in The Brisbane Courier mentioned that E.J. Bennett had invested in a property in the area in 1864. Little information of the fact is available. Given the fact that the lessee or owner of the property was not required to reside at the property (that was established in the Land act 1868) Edward would have lived in Brisbane and had the property supervised by ‘manager’.

Any information about Edward’s ownership or accounts of the property is greatly appreciated

The Brisbane Courier / Thu 16 Nov 1865

The Brisbane Courier / Thu 15 Feb 1866

Hello, I’m interested in your interest in “Noya” which is at the current Mt Warren Park. Are you aware of E.J Bennett’s connection to the early settlers of the area in Beenleigh? I volunteer at the Beenleigh Historical Village in their local stories project.

you forgot to mention when the water main burst while they were building the overpass